Pico Pico - Intro

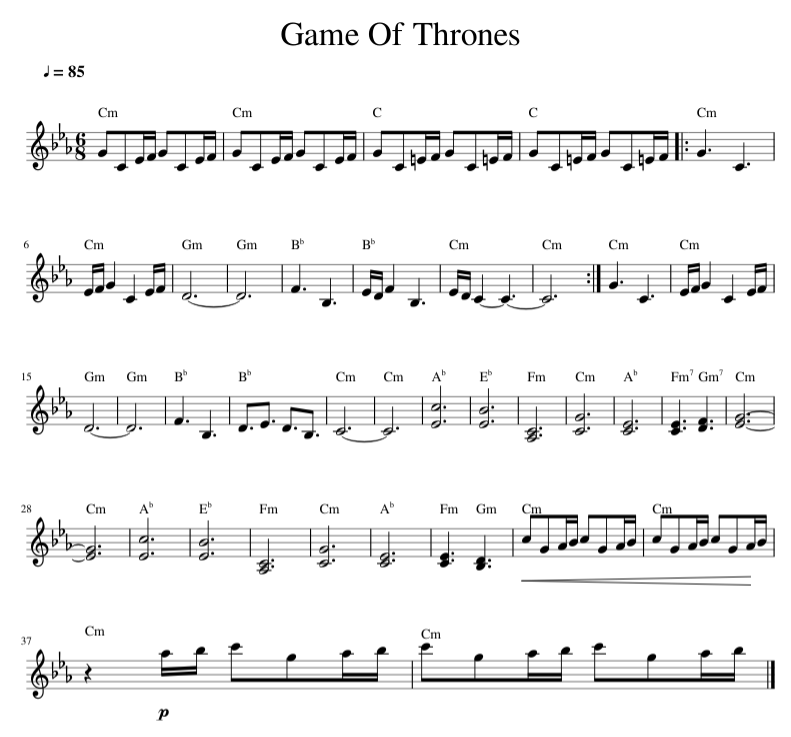

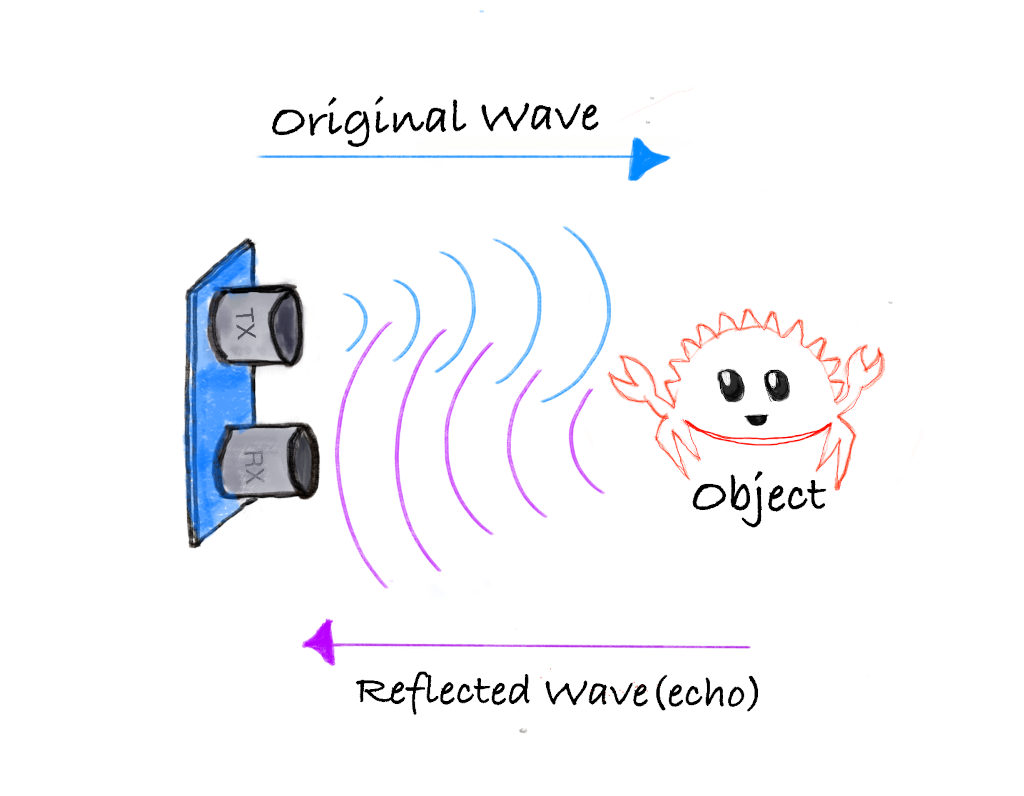

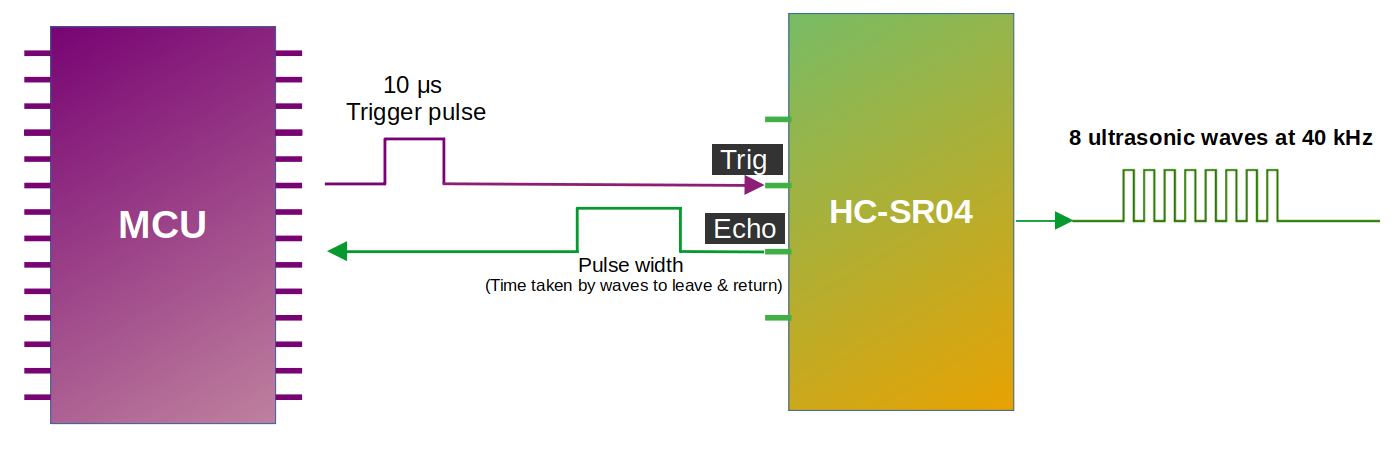

In this book, we use the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 and program it in Rust to explore various exciting projects. You’ll work on exercises like dimming an LED, controlling a servo motor, measuring distance with an ultrasonic sensor, displaying the Ferris (🦀) image on an OLED display, using an RFID reader, playing songs on a buzzer, turning on an LED when the room light is off, measuring temperature, and much more.

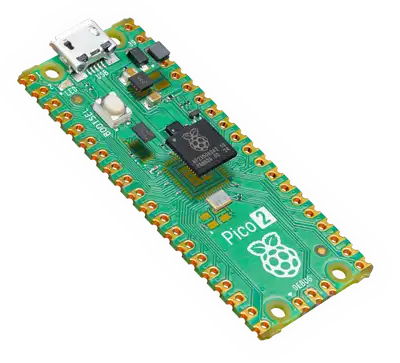

Meet the hardware - Pico 2

We will be using the Raspberry Pi Pico 2, which is based on the new RP2350 chip. It offers dual-core flexibility with support for ARM Cortex-M33 cores and optional Hazard3 RISC-V cores. By default, it operates using the standard ARM cores, but developers can choose to experiment with the RISC-V architecture if needed.

You find more details from the official website.

Note

There is an older Raspberry Pi Pico that uses the RP2040 chip. In this book, we will be using the newer Pico 2 with the RP2350 chip. When buying hardware, make sure to get the correct one!

There is also a variant called the Pico 2 W, which includes Wi‑Fi and Bluetooth capabilities and is powered by the RP2350 chip. However, it is not fully compatible with the examples we’ve provided. If you want to follow along without adjustments, we recommend using the standard Pico 2 (non‑wireless) version. If you choose to buy the Pico 2 W or already have one, you still can follow along. Expect small differences, such as the onboard LED being used by Wi-Fi by default, but the core concepts remain the same.

Datasheets

For detailed technical information, specifications, and guidelines, refer to the official datasheets:

License

The Pico Pico book(this project) is distributed under the following licenses:

- The code samples and free-standing Cargo projects contained within this book are licensed under the terms of both the MIT License and the Apache License v2.0.

- The written prose contained within this book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA v4.0 license.

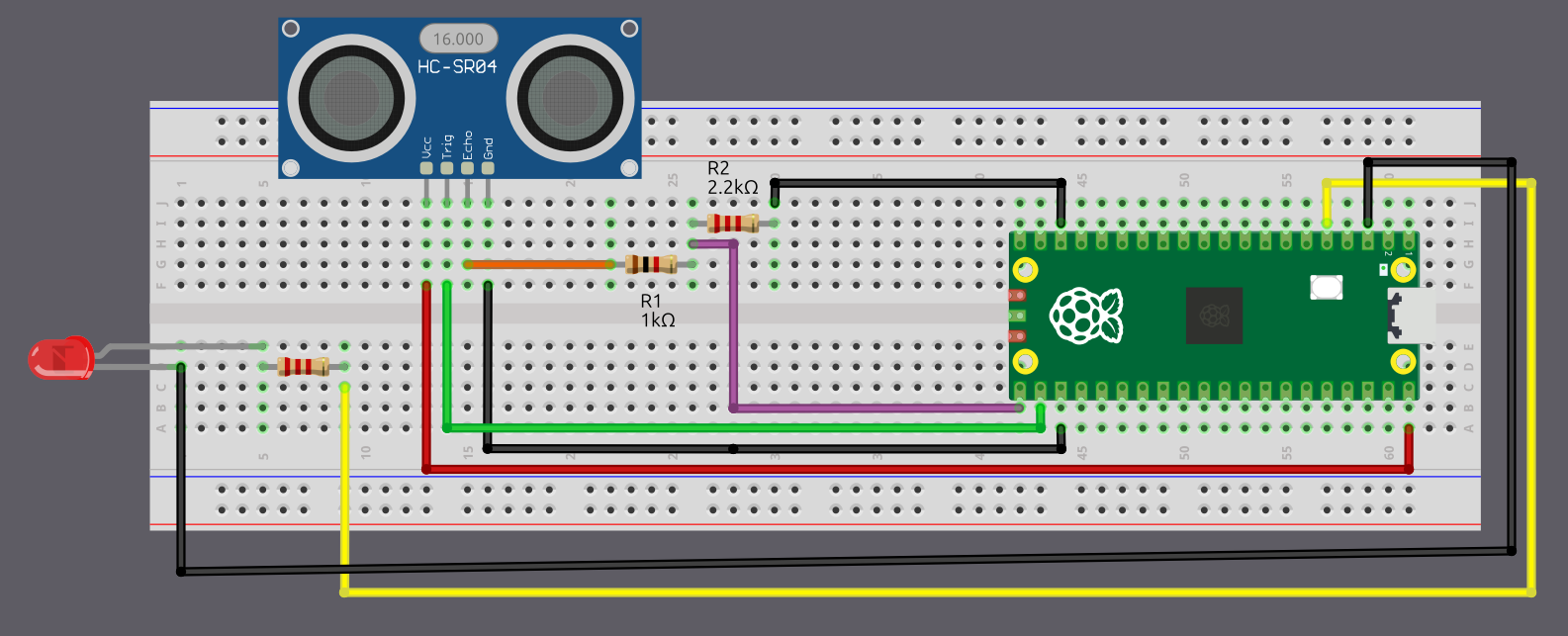

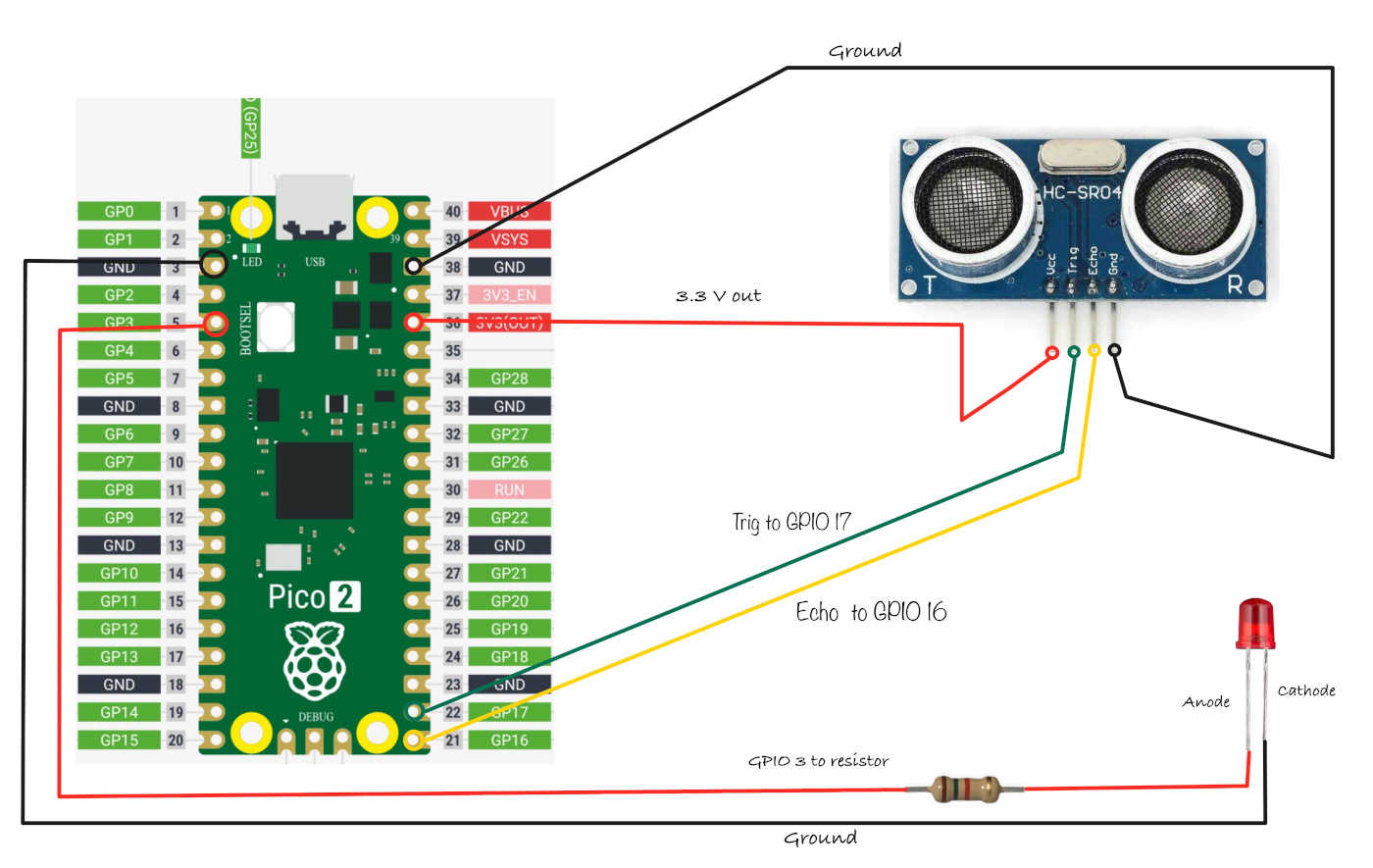

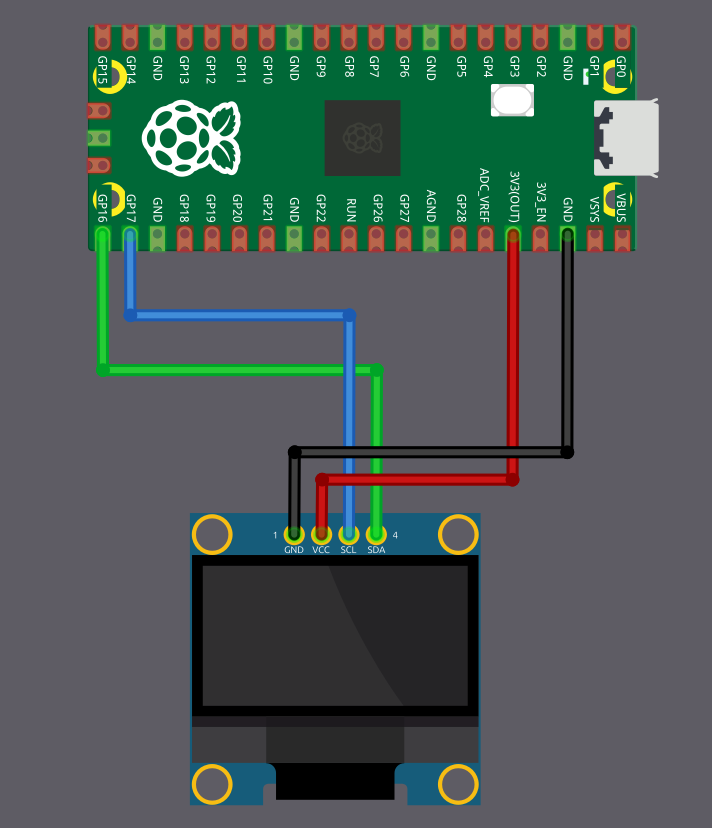

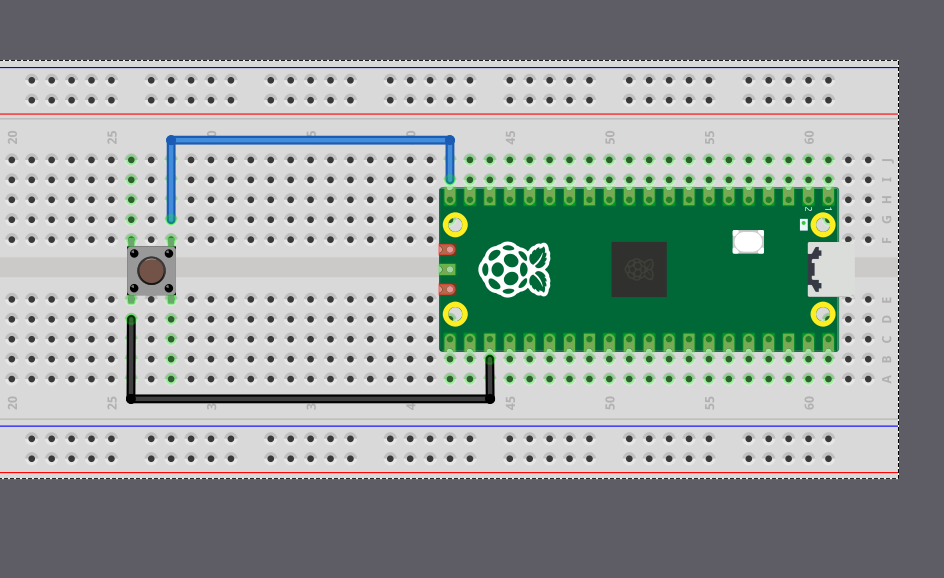

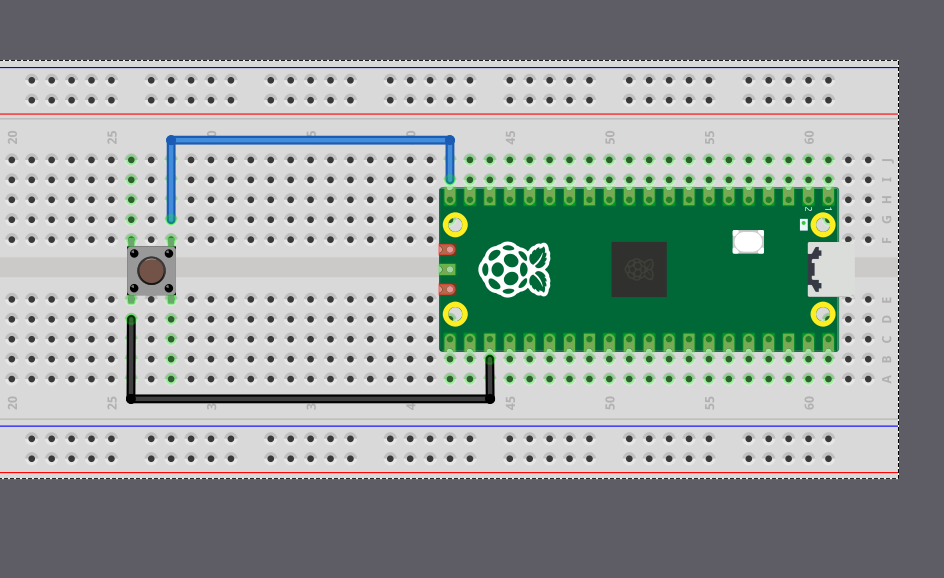

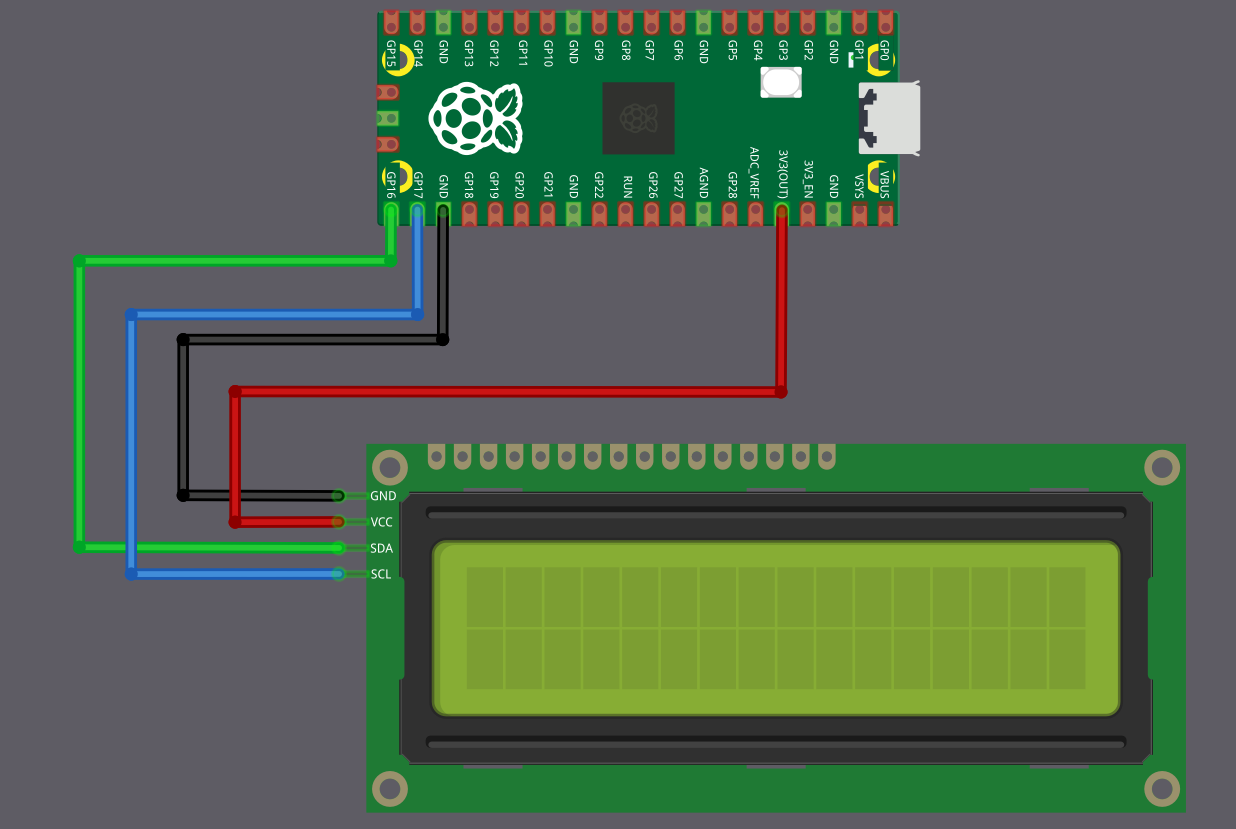

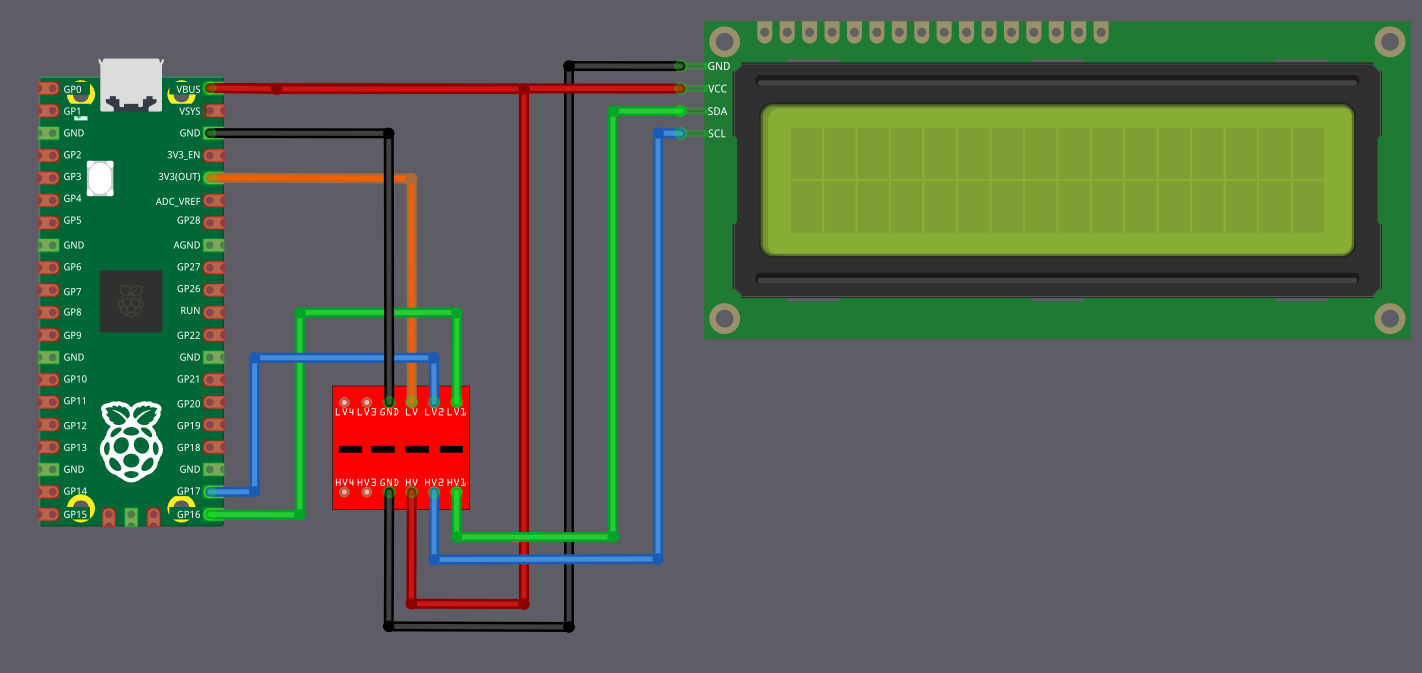

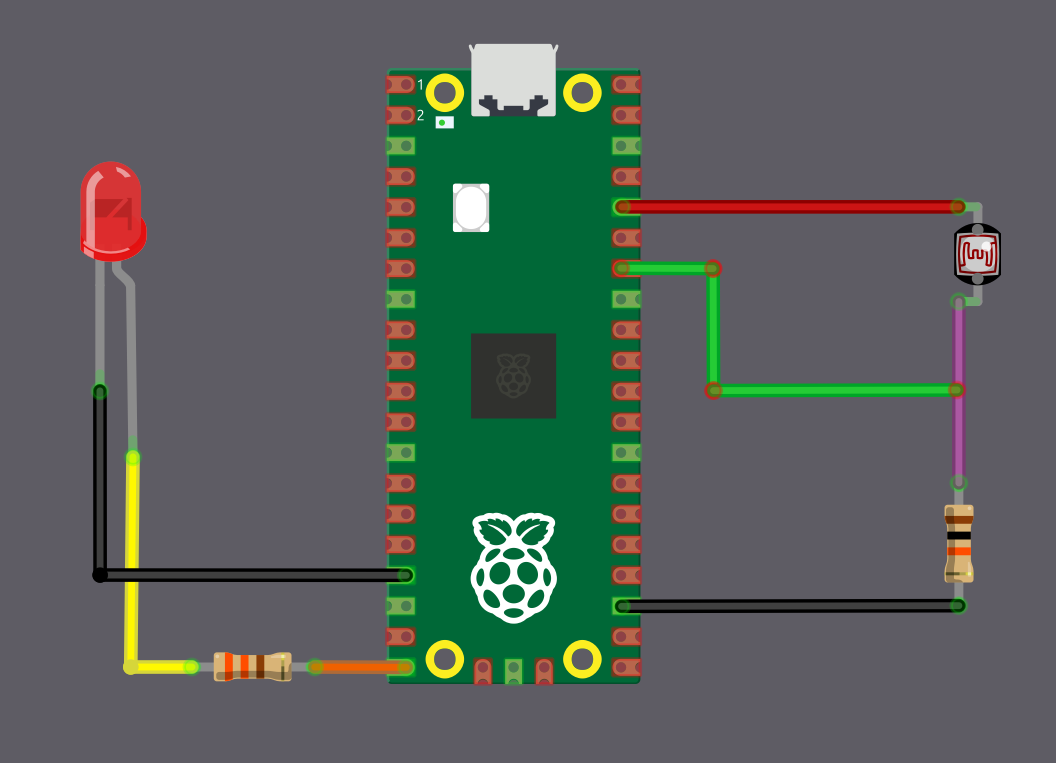

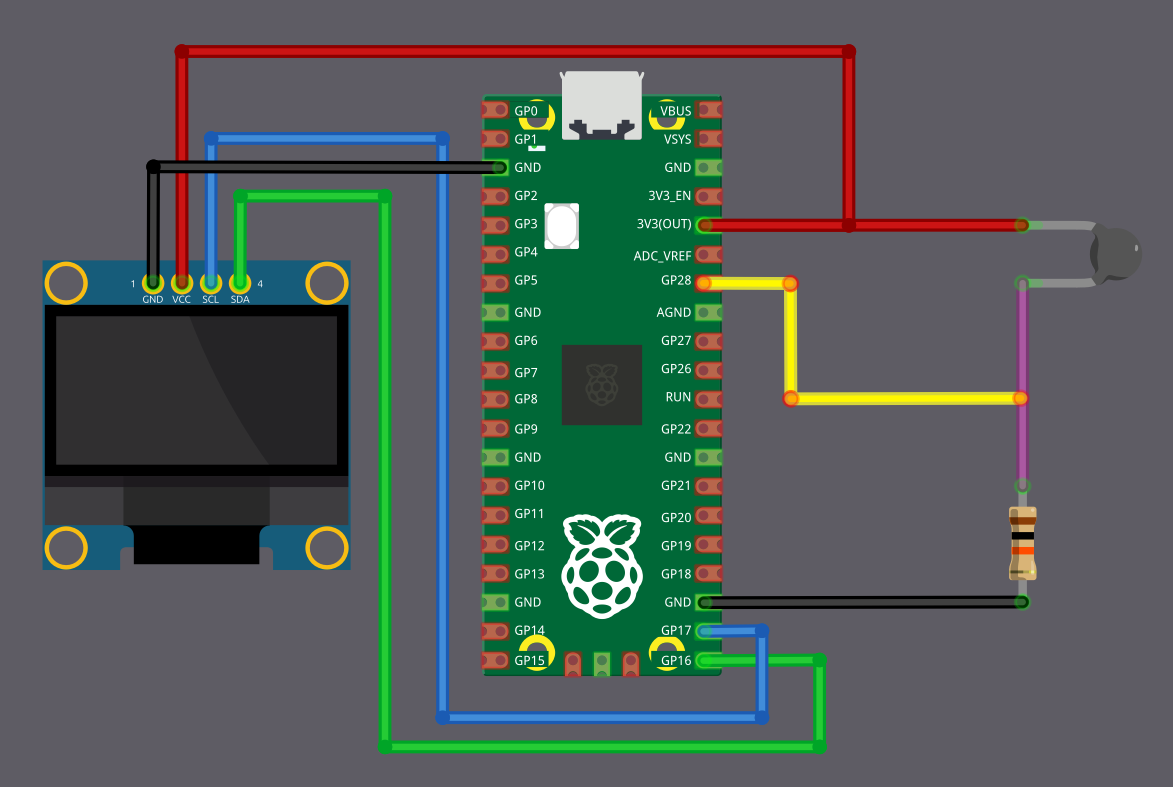

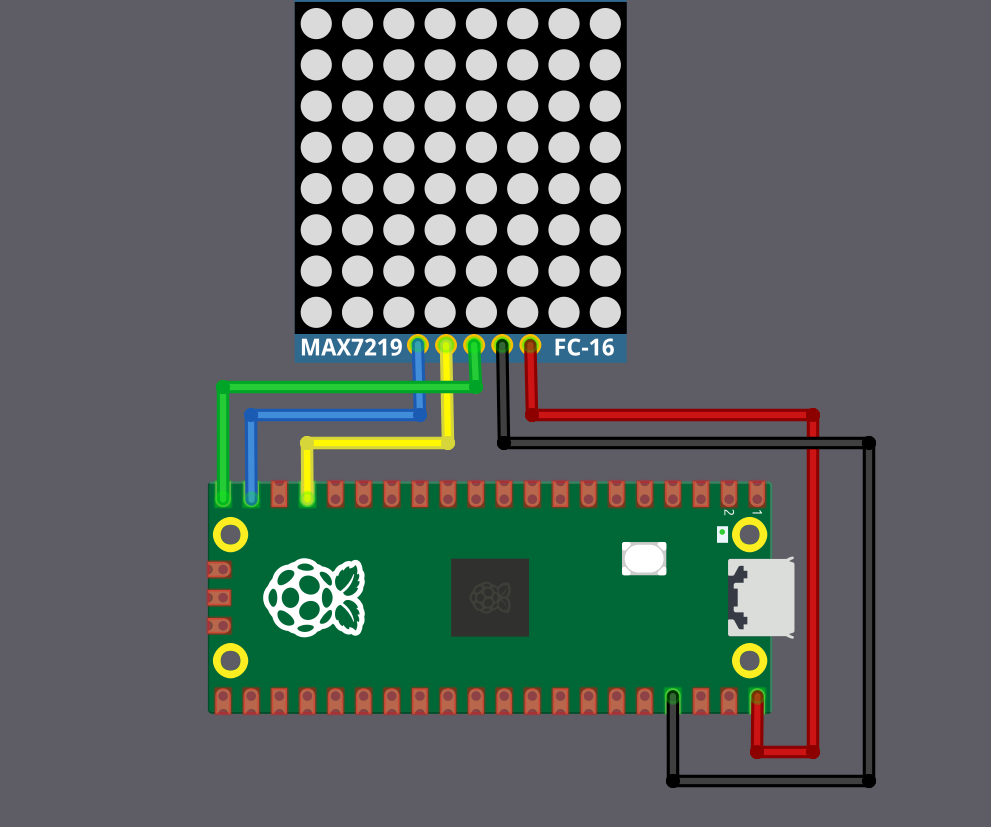

- Circuit diagrams in this book were created with Fritzing.

Support this project

You can support this book by starring this project on GitHub or sharing this book with others 😊

Disclaimer

The experiments and projects shared in this book have worked for me, but results may vary. I’m not responsible for any issues or damage that may occur while you’re experimenting. Please proceed with caution and take necessary safety precautions.

Additional Hardware

In this section we will look at some of the extra hardware you might use along with the Raspberry Pi Pico.

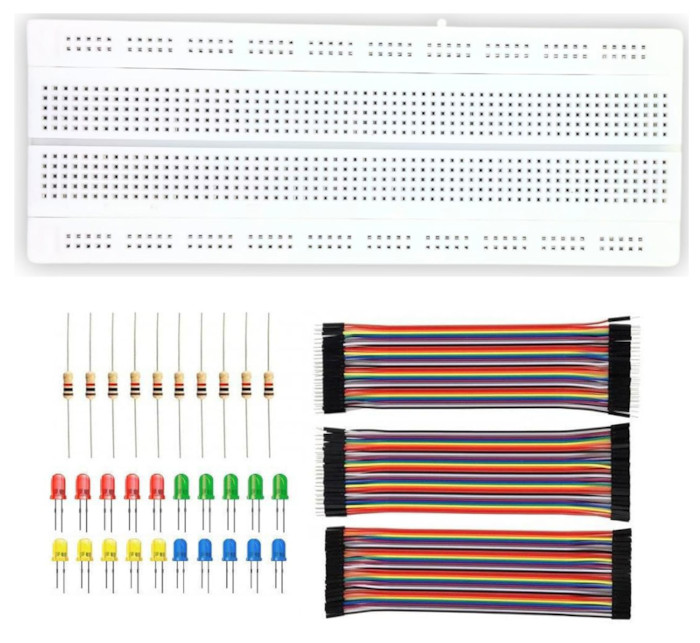

Electronic kits

You can start with a basic electronics kit or buy components as you need them. A simple, low cost kit is enough to begin, as long as it includes resistors, jumper wires, and a breadboard. These are required throughout the lessons.

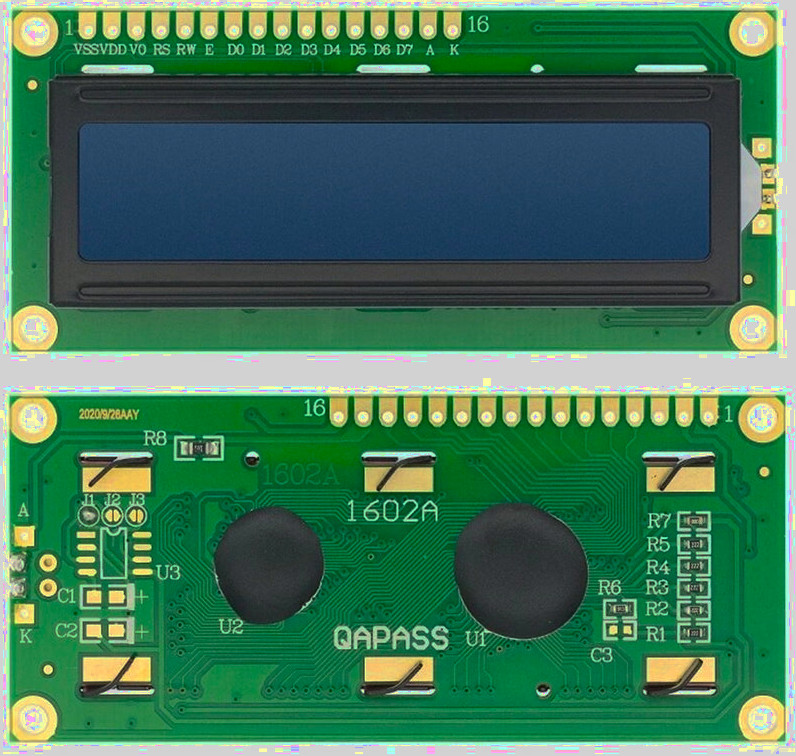

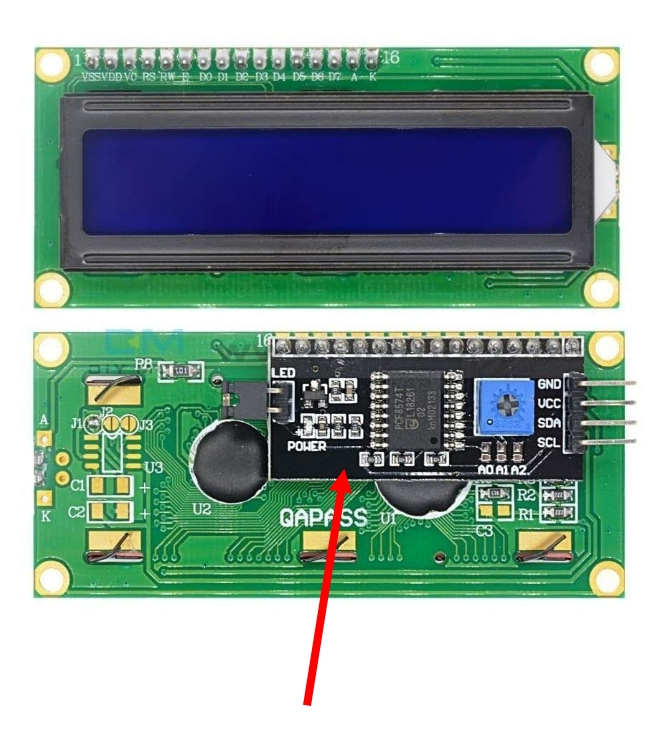

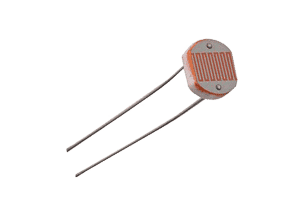

Additional components used in this book include LEDs, the HC SR04 ultrasonic sensor, active and passive buzzers, the SG90 micro servo motor, an LDR, an NTC thermistor, the RC522 RFID reader, a micro SD card adapter, the HD44780 display, and a joystick module.

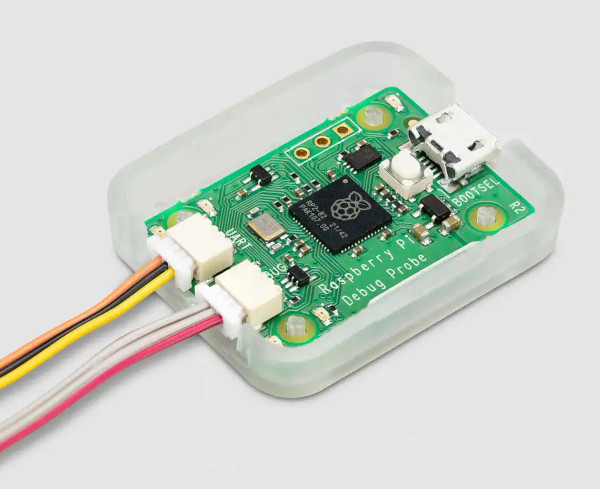

Optional Hardware: Debug Probe

The Raspberry Pi Debug Probe makes flashing the Pico 2 much easier. Without it you must press the BOOTSEL button each time you want to upload new firmware. The probe also gives you proper debugging support, which is very helpful.

This tool is optional. You can follow the entire book without owning one(except the one specific to debug probe). When I first started with the Pico, I worked without a probe and only bought it later.

How to decide?

If you are on a tight budget, you can skip it for now because its price is roughly twice the cost of a Pico 2. If the cost is not an issue, it is a good purchase and becomes very handy. You can also use another Pico as a low cost debug probe if you have a second board available.

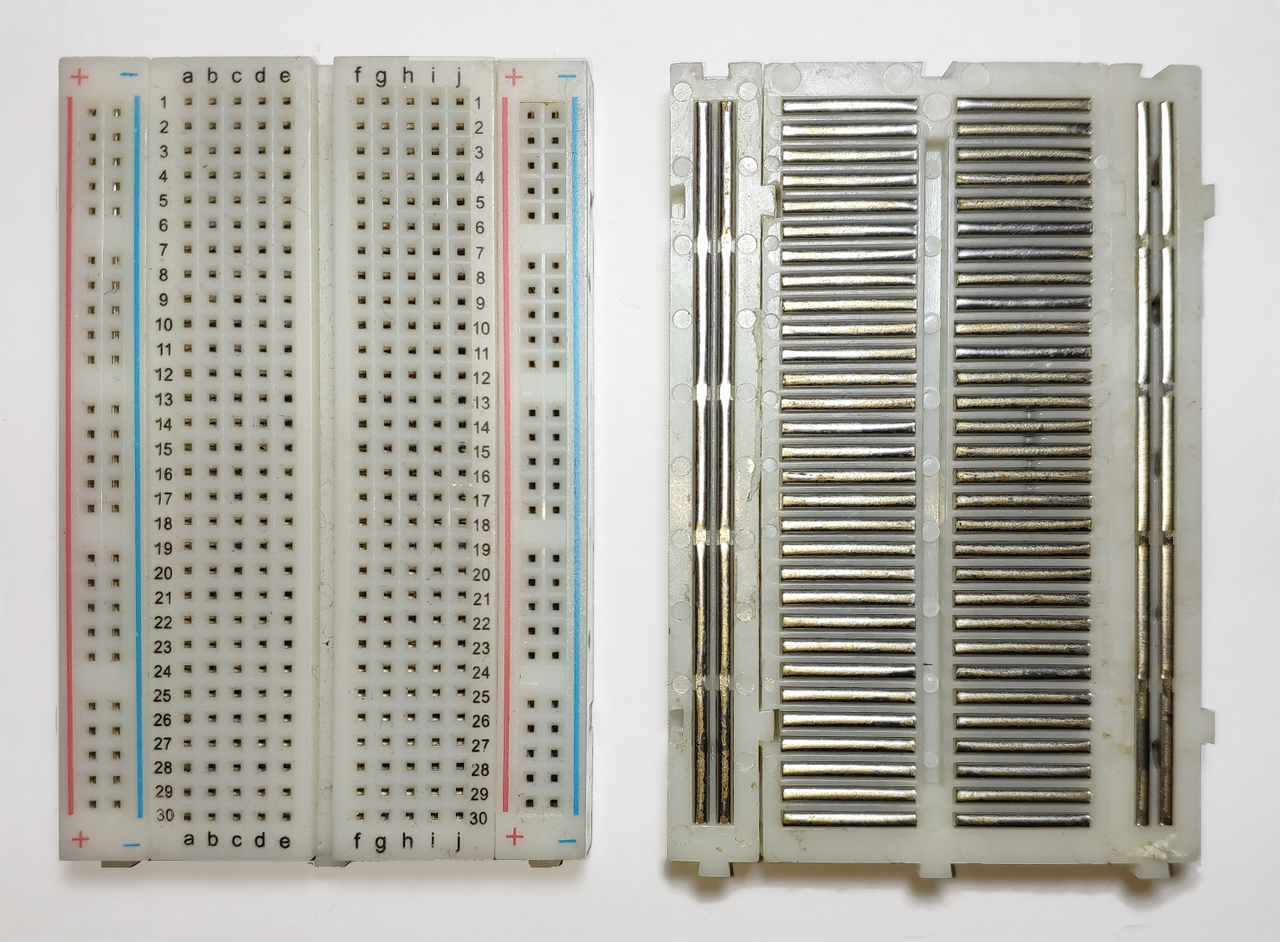

Breadboard

A breadboard is a small board that helps you build circuits without soldering. It has many holes where you can plug in wires and electronic parts. Inside the board, metal strips connect some of these holes. This makes it easy to join parts together and complete a circuit.

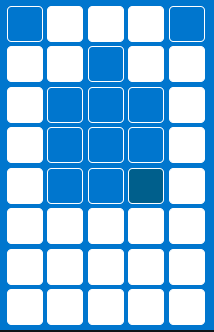

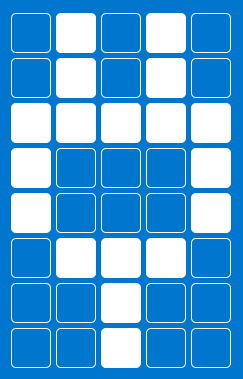

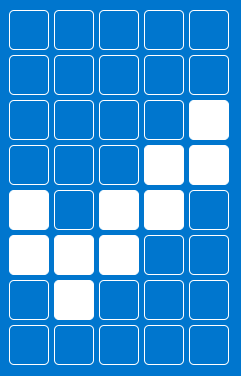

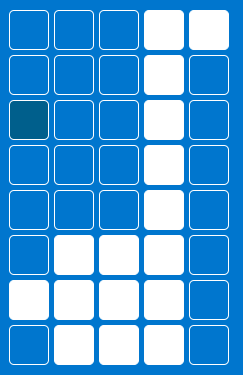

The picture shows how the holes are connected inside the breadboard.

Power rails

The long vertical lines on both sides are called power rails. People usually connect the power supply to the rail marked with “+” and the ground to the rail marked with “-”. Each hole in a rail is connected from top to bottom.

Let’s say you want to give power to many parts. You only need to connect your power source (for example, 3.3V or 5V) to one point on the “+” rail. After that, you can use any other hole on the same rail to power your components.

Middle area

The middle part of the breadboard is where you place most of your components. The holes here are connected in small horizontal rows. Each row has five holes that are linked together inside the board.

As you can see in the image, each row is separate, and the groups marked as a b c d e are separated from the groups marked as f g h i j. The center gap divides these two sides, so the connections do not cross from one side to the other.

Here are some simple examples:

- If you plug a wire into 5a and another wire into 5c, they are connected because they are in the same row.

- If you plug one wire into 5a and another into 5f, they are

notconnected because they are on different sides of the gap. - If you plug one wire into 5a and the other into 6a, they are

notconnected because they are in different rows.

Components

In this book, we will use various external components together with the Pico to build examples and experiments. These components are used to interact with the outside world, such as reading inputs, controlling outputs, and displaying information.

Some components are simple parts like LEDs, buttons, resistors, LDRs, and thermistors. Others are assembled units such as displays, sensors, and interface devices that connect to the Pico using a small number of pins.

Important

Some components may require soldering, for example attaching header pins to boards such as displays or sensor modules. Many parts are also available in pre-soldered form.

If a component does not have pins attached, you will need to solder them before use. Soldering is a practical skill in embedded work, so take your time and follow basic safety precautions.

This section only provides an overview of the components that appear throughout the book. Detailed explanations, wiring, and code examples are covered later in their respective chapters. You do not need to collect all components in advance. You can add them gradually as you progress through the book.

Components Used in This Book

Component names are provided for reference. Before purchasing, check the corresponding chapter to ensure the module type and pin layout match the examples used in this book.

- Breadboard

- Jumper wires (male-male, male-female)

- LED

- Resistors (common values: 330 ohm, 1k ohm, 2.2k ohm, 10k ohm)

- Push button (tactile switch)

- LDR (Light Dependent Resistor)

- NTC Thermistor (10k)

- OLED display (SSD1306, 128x64, I2C)

- LCD display (16x2, HD44780 compatible)

- Ultrasonic sensor (HC-SR04 / HC-SR04+)

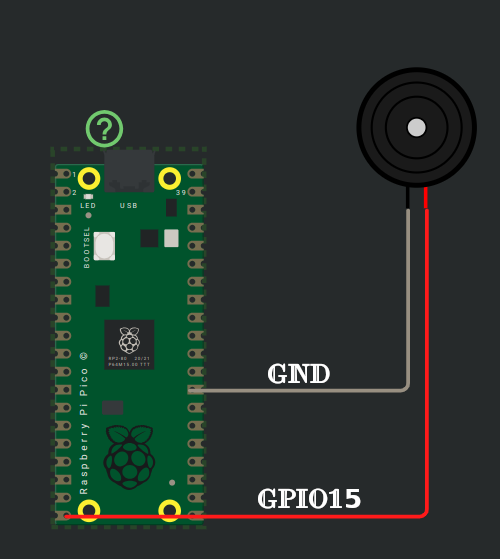

- Buzzer (active and passive)

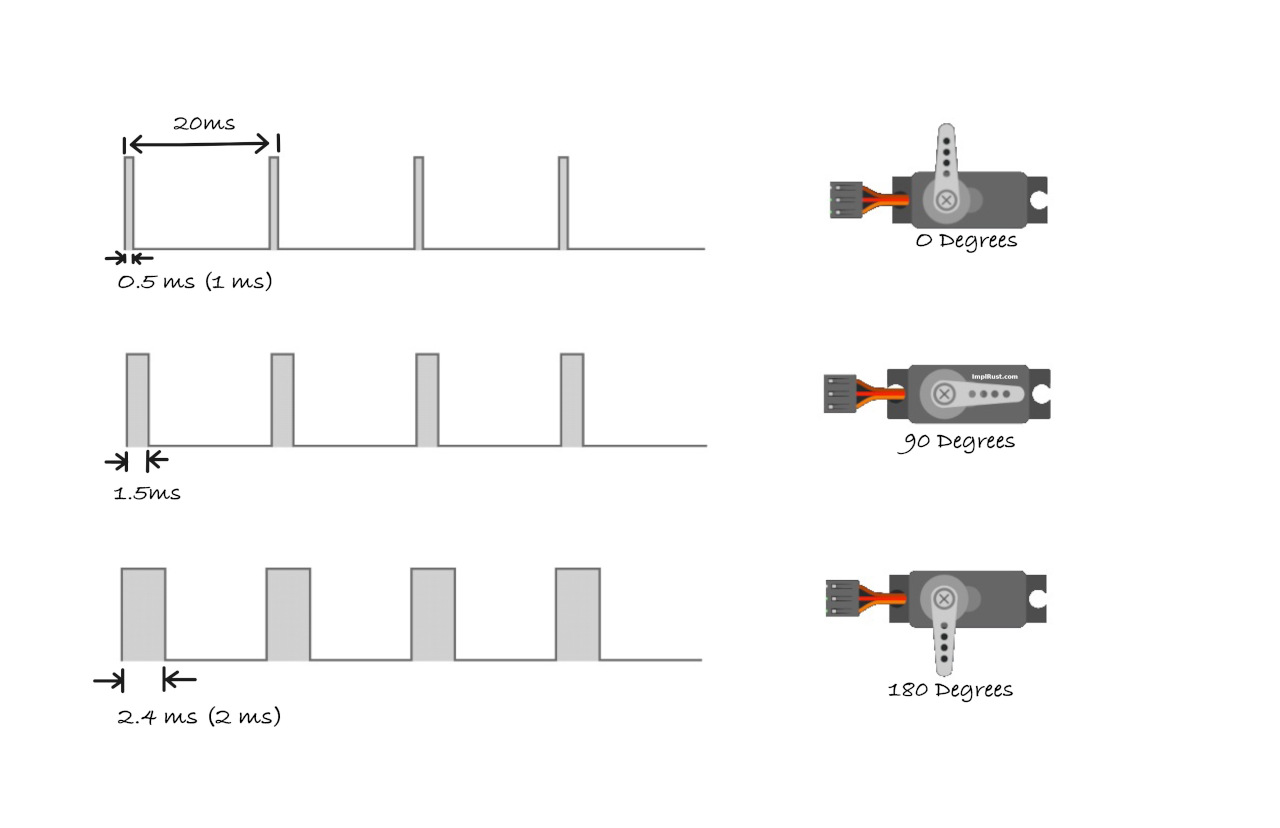

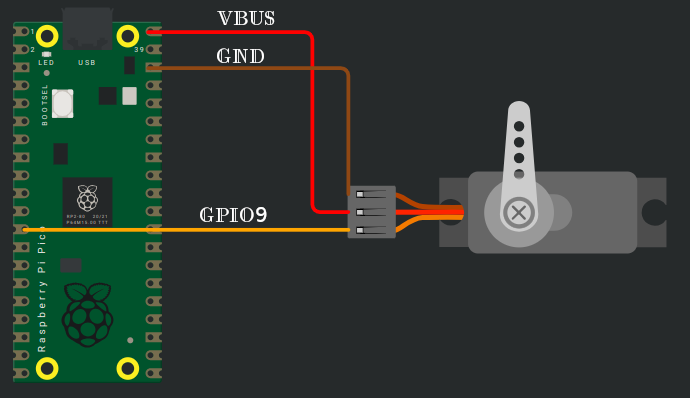

- Servo motor (SG90)

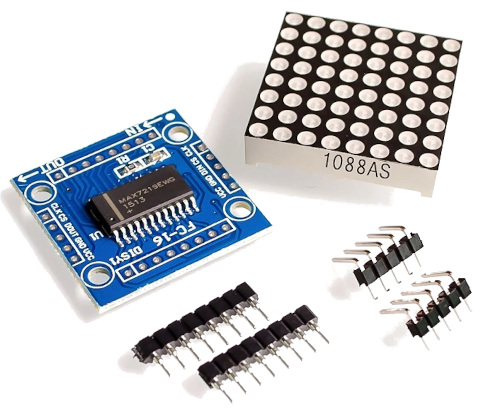

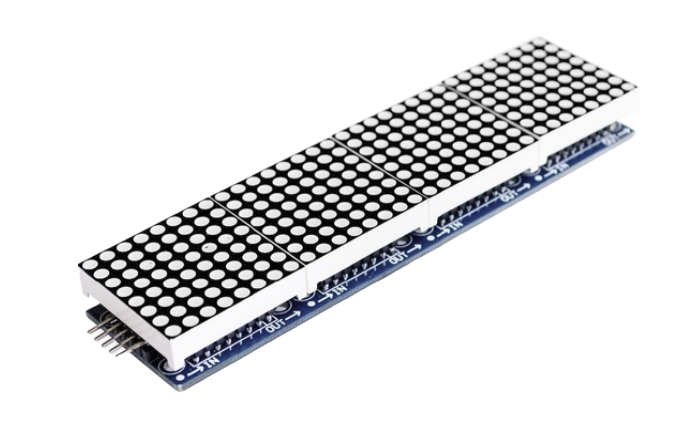

- MAX7219 8X8 Dot LED Matrix Display Module

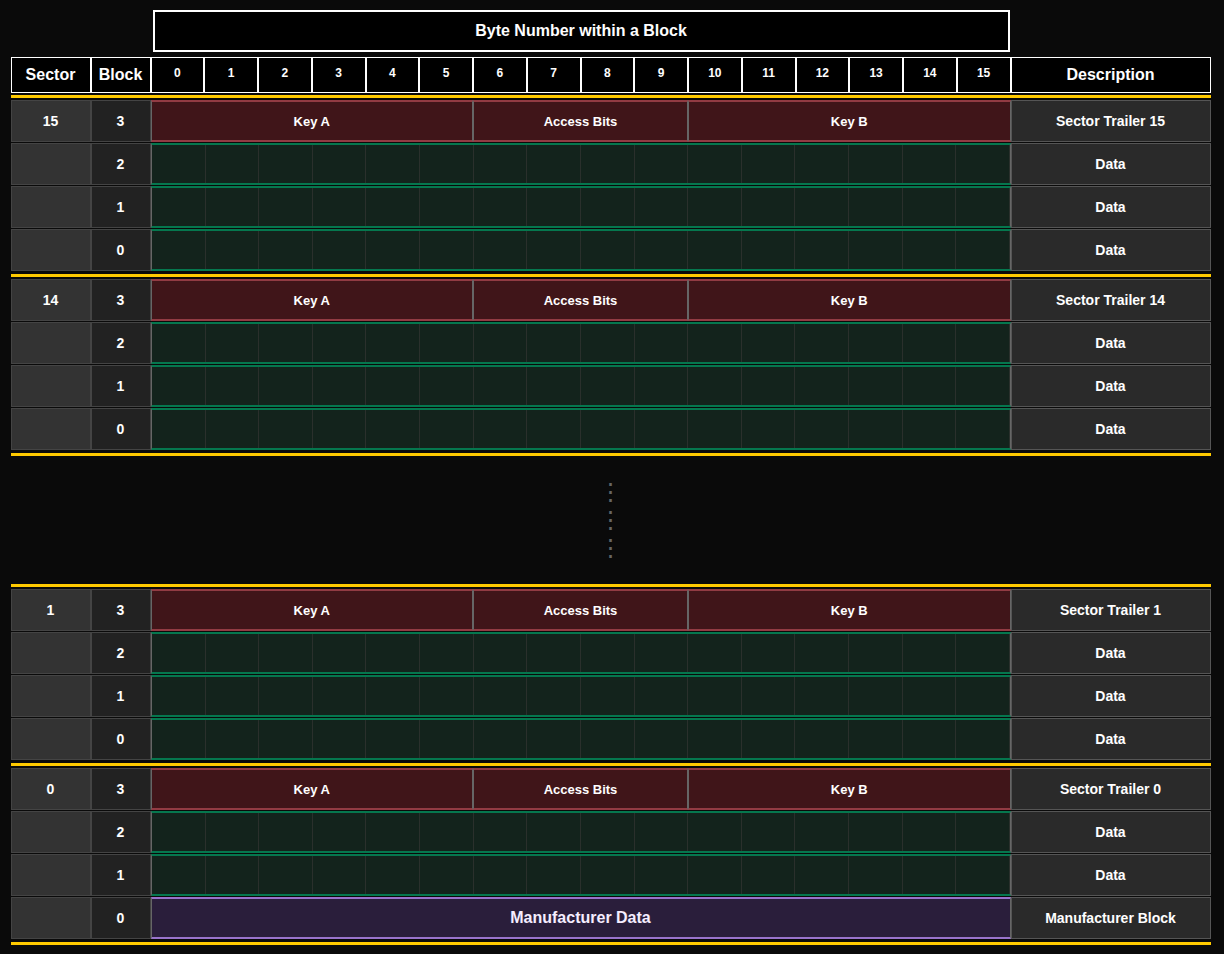

- RFID module (RC522)

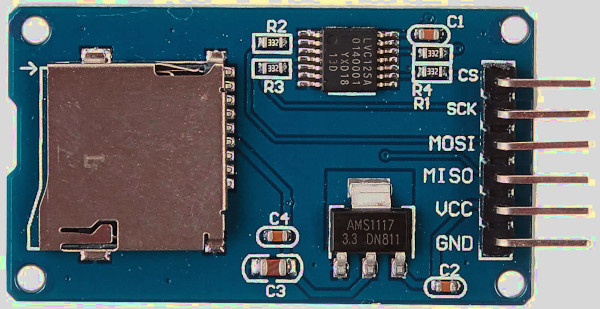

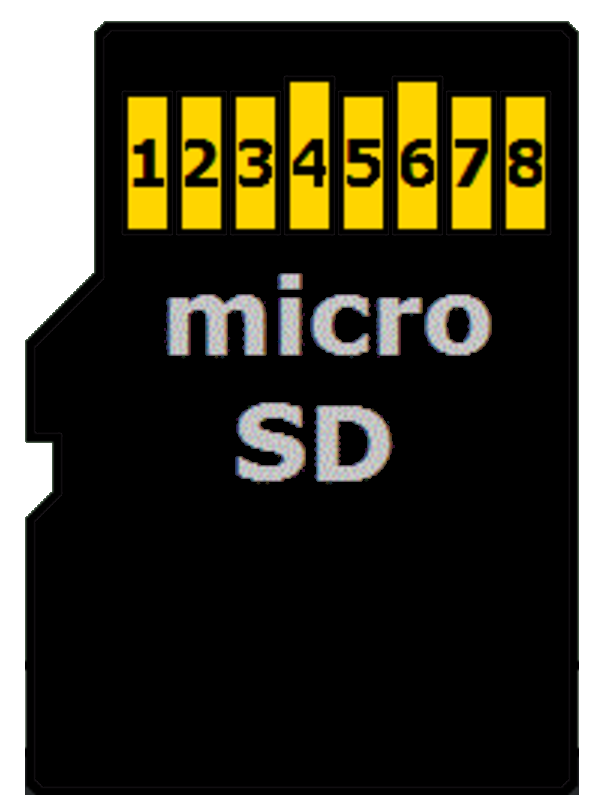

- Micro SD Card Reader Module (SPI)

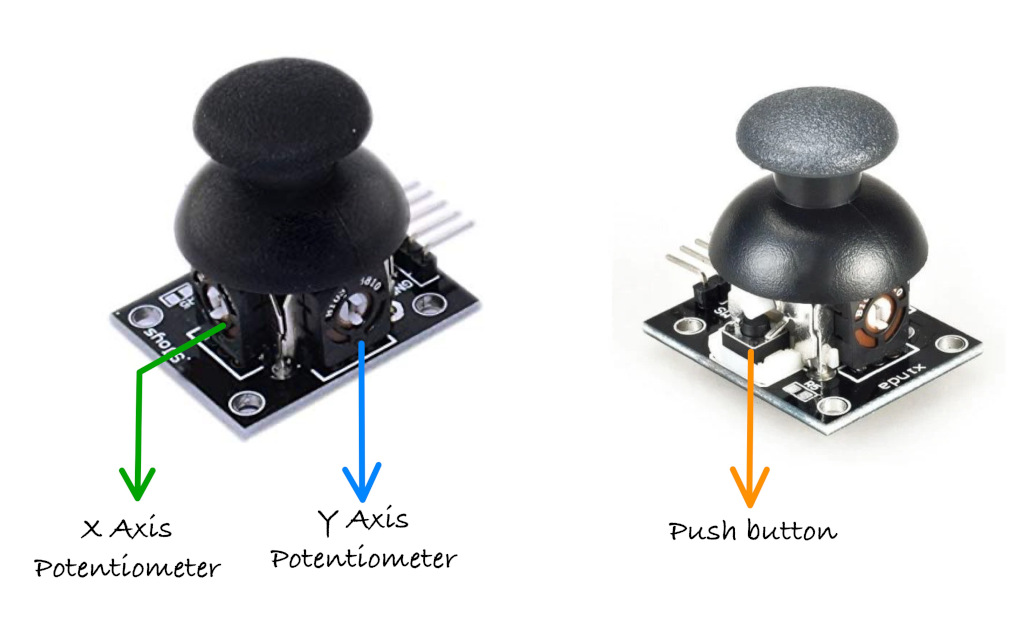

- Joystick module (PS2 type)

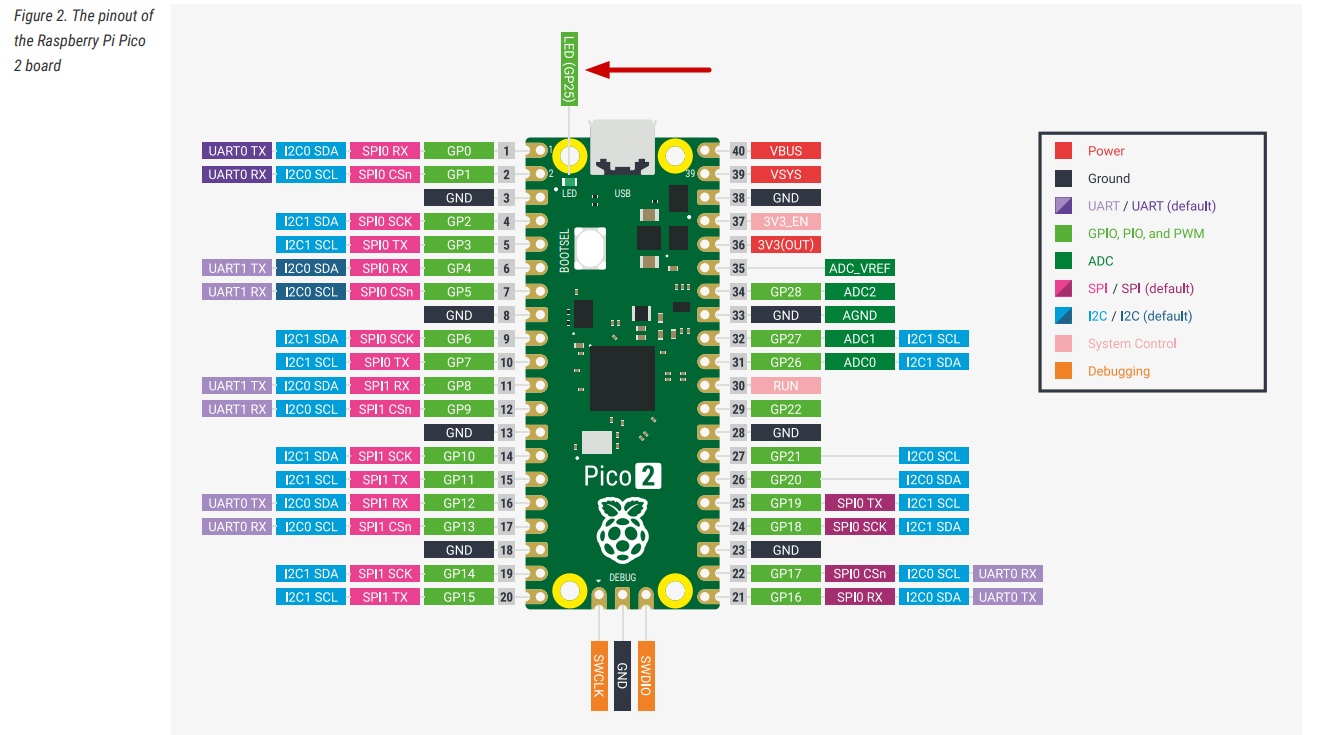

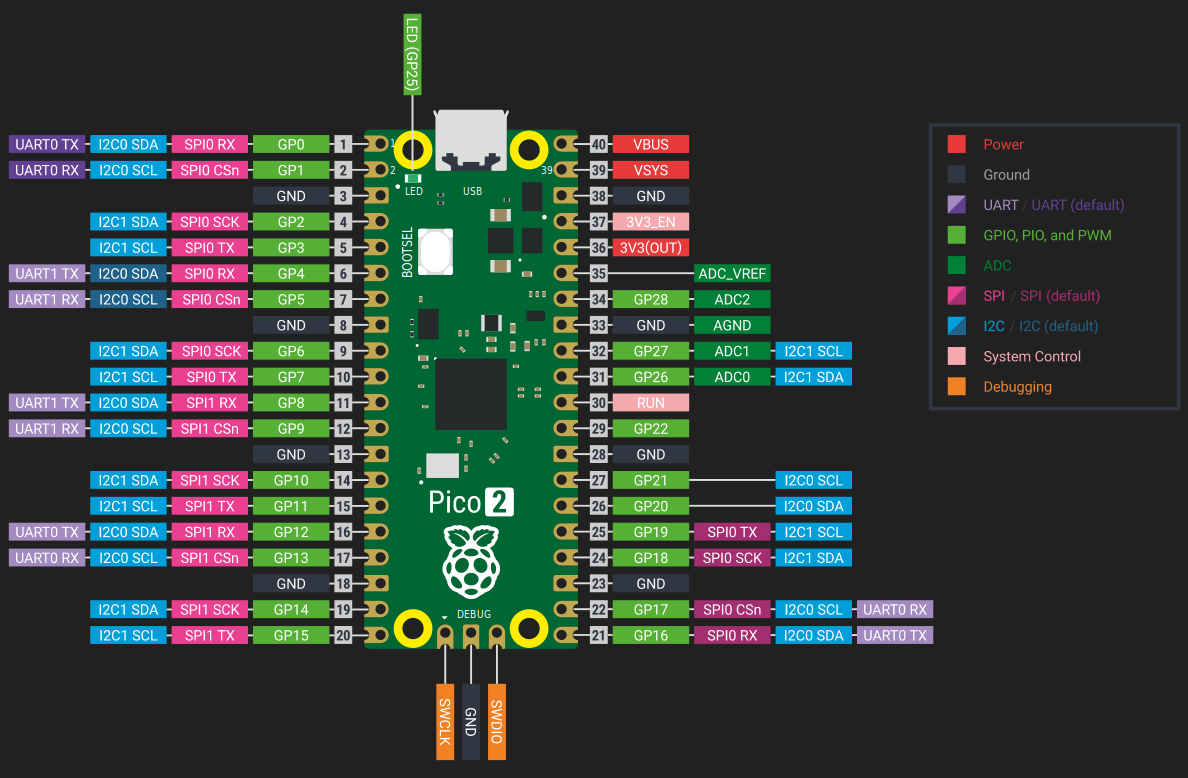

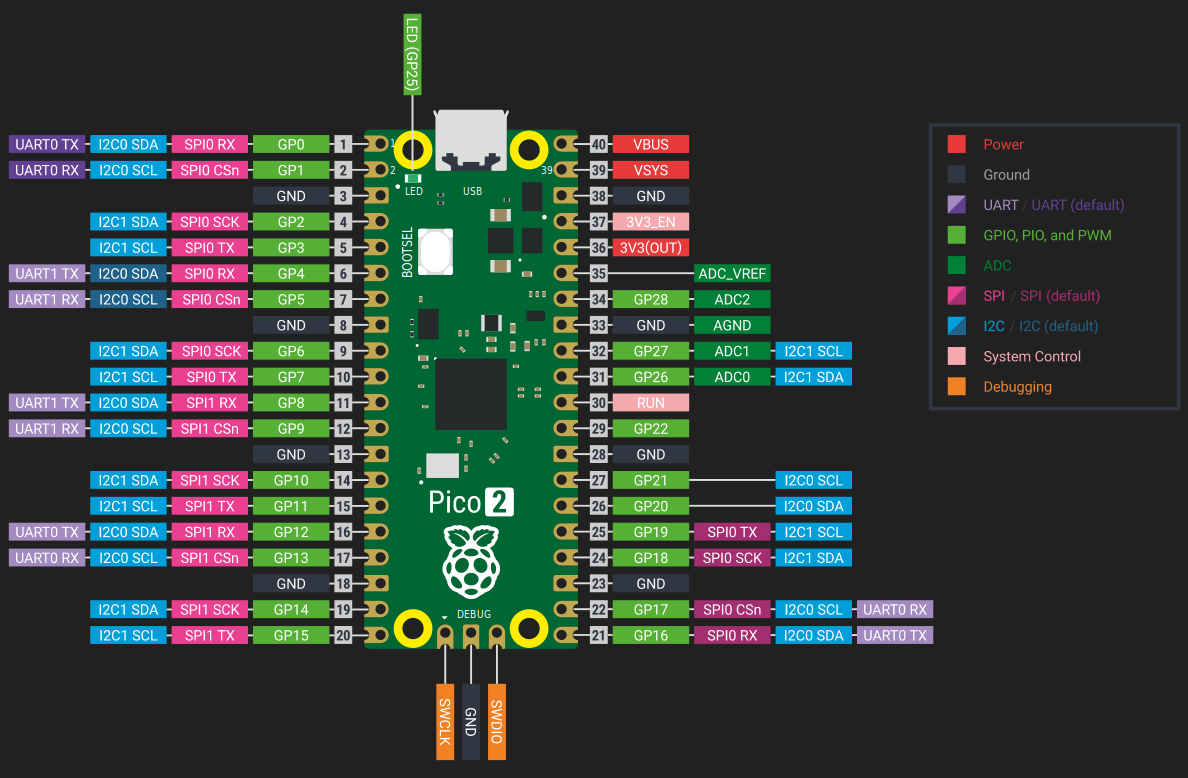

Raspberry Pi Pico 2 Pinout Diagram

Tip

You don’t need to memorize or understand every pin right now. We will refer back to this section as needed while working through the exercises in this book.

Power Pins

Power pins are essential for keeping your Raspberry Pi Pico 2 running and supplying electricity to the sensors, LEDs, motors, and other components you connect to it.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 has the following power pins. These are marked in red (power) and black (ground) in the pinout diagrams. These pins are used to supply power to the board and to external components.

-

VBUS is connected to the 5V coming from the USB port. When the board is powered over USB, this pin will carry about 5V. You can use it to power small external circuits, but it’s not suitable for high-current loads.

-

VSYS is the main power input for the board. You can connect a battery or regulated supply here with a voltage between 1.8V and 5.5V. This pin powers the onboard 3.3V regulator, which supplies the RP2350 and other parts.

-

3V3(OUT) provides a stable 3.3V output from the onboard regulator. It can be used to power external components like sensors or displays, but it’s best to limit the current draw to under 300mA.

-

GND pins are used to complete electrical circuits and are connected to the system ground. The Pico 2 provides multiple GND pins spread across the board for convenience when connecting external devices.

GPIO Pins

When you want your microcontroller(i.e Pico) to interact with the world; like turning on lights, reading button presses, sensing temperature, or controlling motors; you need a way to connect and communicate with these external components. That’s exactly what GPIO pins do: they’re your Raspberry Pi Pico 2’s connection points to external components.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 includes 26 General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins, labeled GPIO0 through GPIO29, though not all numbers are exposed on the headers. These GPIOs are highly flexible and can be used to read inputs like switches or sensors, or to control outputs such as LEDs, motors, or other devices.

All GPIOs operate at 3.3V logic. This means any input signal you connect should not exceed 3.3 volts, or you risk damaging the board. While many GPIOs support basic digital I/O, some also support additional functions like analog input (ADC), or act as communication lines for protocols like I2C, SPI, or UART.

Pin Numbering

Each GPIO pin can be referenced in two ways: by its GPIO number (used in software) and by its physical pin location on the board. When writing code, you will use the GPIO number (like GPIO0). When connecting wires, you need to know which GPIO is connected to which physical pin.

GPIO25 is special, it is connected to the onboard LED and can be controlled directly in code without any external wiring.

For example, when your code references GPIO0, you’ll connect your wire to physical pin 1 on the board. Similarly, GPIO2 connects to physical pin 4.

ADC Pins

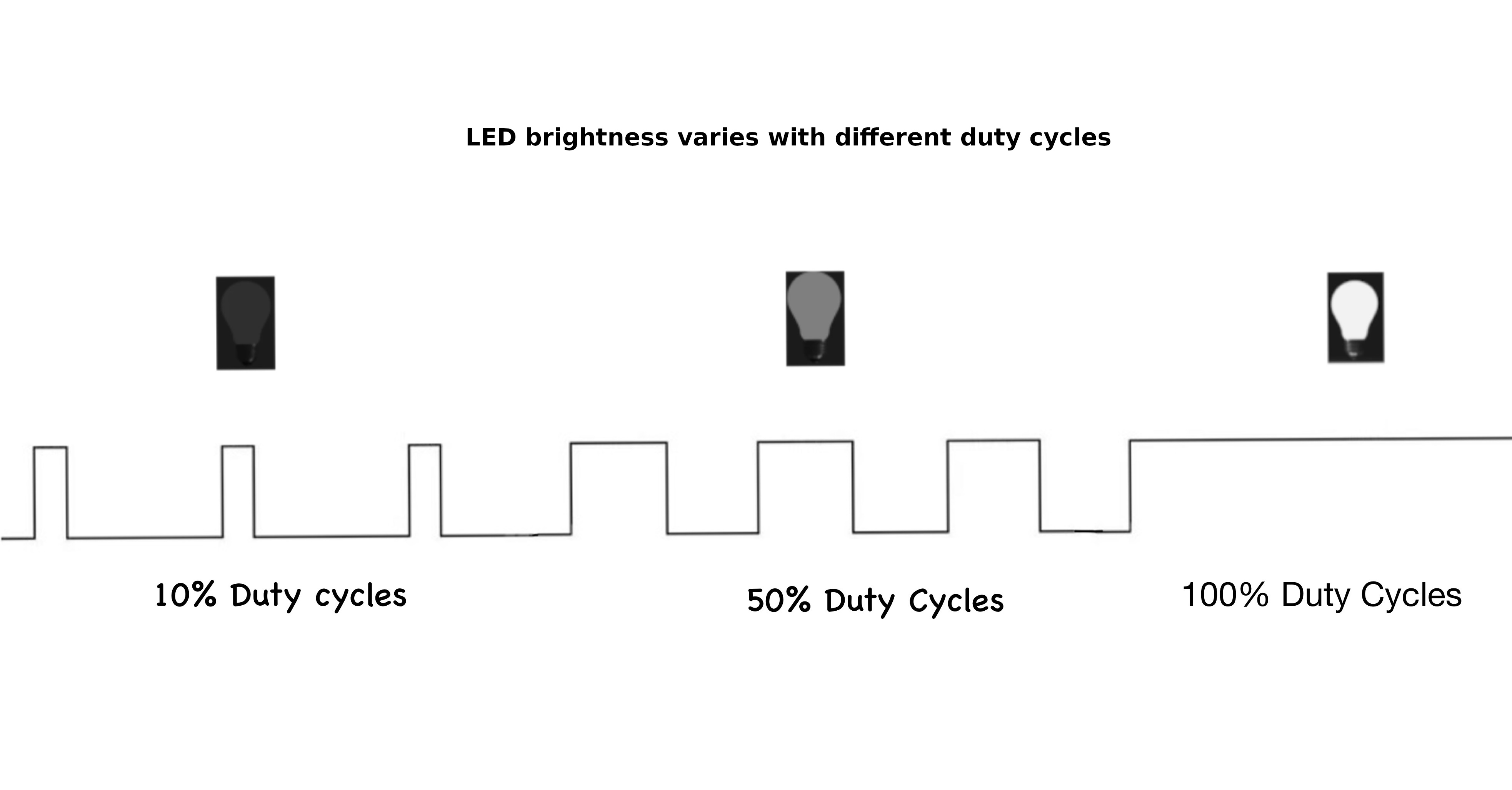

Most pins on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 work with simple on/off signals; perfect for things like LEDs or buttons. But what if you want to measure how bright a room is to automatically turn on lights? Or monitor soil moisture to water plants? Or read how far someone turned a volume knob? These tasks need pins that can sense gradual changes, not just on/off states.

Most of the pins on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 are digital - they can only read or send values like ON (high) or OFF (low). But some devices, like light sensors or temperature sensors, produce signals that change gradually. To understand these kinds of signals, we need special pins called ADC pins.

ADC stands for Analog-to-Digital Converter. It takes a voltage and turns it into a number your program can understand. For example, a voltage of 0V might become 0, and 3.3V might become 4095 (the highest number the ADC can produce, since it uses 12-bit resolution). We will take a closer look at the ADC later in this book.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 has three ADC-capable pins. These are GPIO26, GPIO27, and GPIO28, which correspond to ADC0, ADC1, and ADC2 respectively. You can use these pins to read analog signals from sensors such as light sensors, temperature sensors.

There are also two special pins that support analog readings:

-

ADC_VREF is the reference voltage for the ADC. By default, it’s connected to 3.3V, meaning the ADC will convert anything between 0V and 3.3V into a number. But you can supply a different voltage here (like 1.25V) if you want more precise measurements in a smaller range.

-

AGND is the analog ground, used to provide a clean ground for analog signals. This helps reduce noise and makes your analog readings more accurate. If you’re using an analog sensor, it’s a good idea to connect its ground to AGND instead of a regular GND pin.

I2C Pins

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 supports I2C, a communication protocol used to connect multiple devices using just two wires. It is commonly used with sensors, displays, and other peripherals.

I2C uses two signals: SDA (data line) and SCL (clock line). These two lines are shared by all connected devices. Each device on the bus has a unique address, so the Pico 2 can talk to many devices over the same pair of wires.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 has two I2C controllers: I2C0 and I2C1. Each controller can be mapped to multiple GPIO pins, giving you flexibility depending on your circuit needs.

-

I2C0 can use these GPIOs:

- SDA (data): GPIO0, GPIO4, GPIO8, GPIO12, GPIO16, or GPIO20

- SCL (clock): GPIO1, GPIO5, GPIO9, GPIO13, GPIO17, or GPIO21

-

I2C1 can use these GPIOs:

- SDA (data): GPIO2, GPIO6, GPIO10, GPIO14, GPIO18, or GPIO26

- SCL (clock): GPIO3, GPIO7, GPIO11, GPIO15, GPIO19, or GPIO27

You can choose any matching SDA and SCL pair from the same controller (I2C0 or I2C1).

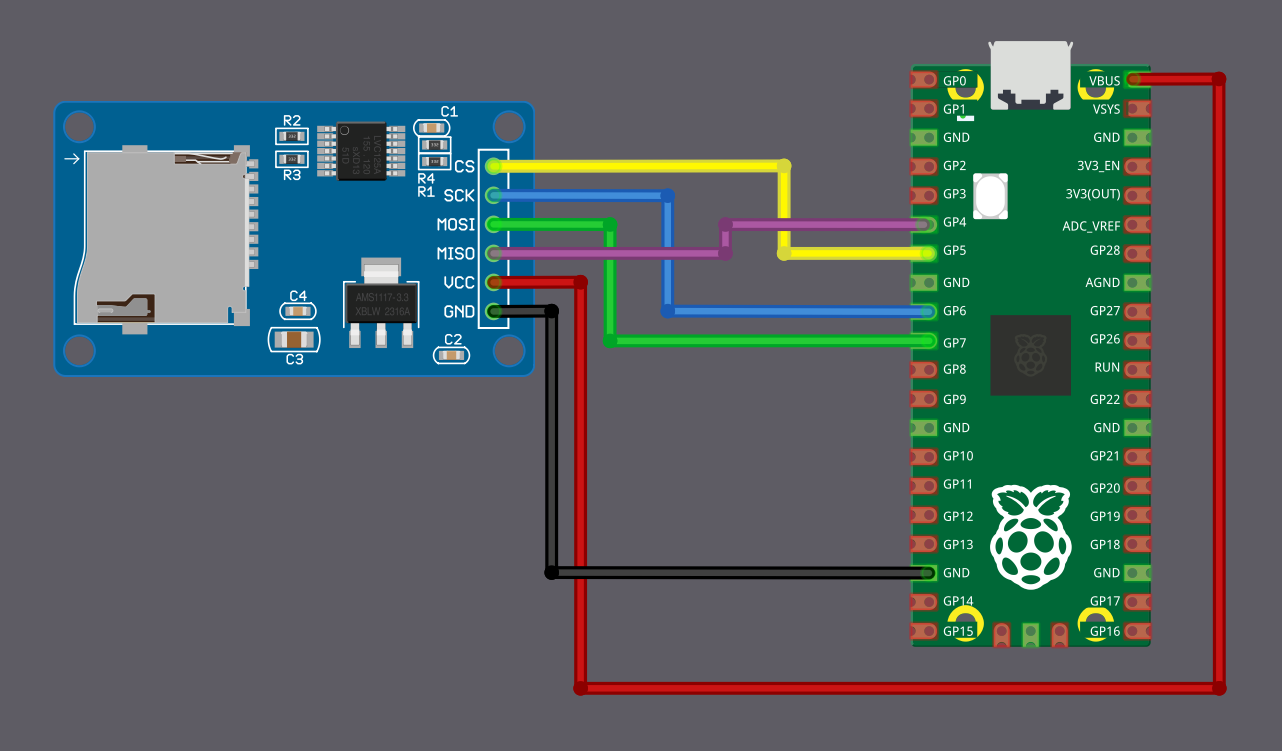

SPI Pins

SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) is another communication protocol used to connect devices like displays, SD cards, and sensors. Unlike I2C, SPI uses more wires but offers faster communication. It works with one controller (like the Pico 2) and one or more devices.

SPI uses four main signals:

- SCK (Serial Clock): Controls the timing of data transfer.

- MOSI (Master Out Slave In): Data sent from the controller to the device.

- MISO (Master In Slave Out): Data sent from the device to the controller.

- CS/SS (Chip Select or Slave Select): Used by the controller to select which device to talk to.

On Pico 2 pinout diagrams, MOSI is labeled as Tx, MISO as Rx, and CS as Csn.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 has two SPI controllers: SPI0 and SPI1. Each can be connected to multiple GPIO pins, so you can choose whichever set fits your circuit layout.

-

SPI0 can use:

- SCK: GPIO2, GPIO6, GPIO10, GPIO14, GPIO18

- MOSI: GPIO3, GPIO7, GPIO11, GPIO15, GPIO19

- MISO: GPIO0, GPIO4, GPIO8, GPIO12, GPIO16

-

SPI1 can use:

- SCK: GPIO14, GPIO18

- MOSI: GPIO15, GPIO19

- MISO: GPIO8, GPIO12, GPIO16

You can choose a group of compatible pins from the same controller depending on your circuit layout. The CS (chip select) pin is not fixed-you can use any free GPIO for that purpose. We will explore how to configure SPI and connect devices in upcoming chapters.

UART Pins

UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter) is one of the simplest ways for two devices to talk to each other. It uses just two main wires:

- TX (Transmit): Sends data out.

- RX (Receive): Receives data in.

UART is often used to connect to serial devices like GPS modules, Bluetooth adapters, or even to your computer for debugging messages.

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 has two UART controllers: UART0 and UART1. Each one can be mapped to several different GPIO pins, giving you flexibility when wiring your circuit.

-

UART0 can use:

- TX: GPIO0, GPIO12, GPIO16

- RX: GPIO1, GPIO13, GPIO17

-

UART1 can use:

- TX: GPIO4, GPIO8

- RX: GPIO5, GPIO9

You need to use a matching TX and RX pin from the same UART controller. For example, you could use UART0 with TX on GPIO0 and RX on GPIO1, or UART1 with TX on GPIO8 and RX on GPIO9.

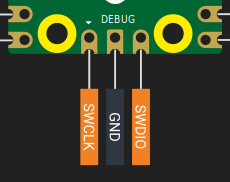

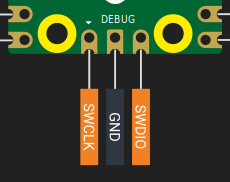

SWD Debugging Pins

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 provides a dedicated 3-pin debug header for SWD (Serial Wire Debug), which is the standard ARM debugging interface. SWD allows you to flash firmware, inspect registers, set breakpoints, and perform real-time debugging.

This interface consists of the following signals:

- SWDIO - Serial data line

- SWCLK - Serial clock line

- GND - Ground reference

These pins are not shared with general-purpose GPIO and are located on a separate debug header at the bottom edge of the board. You will typically use an external debug probe like the Raspberry Pi Debug Probe, CMSIS-DAP adapter, or other compatible tools (e.g., OpenOCD, probe-rs) to connect to these pins.

Onboard Temperature Sensor

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 includes a built-in temperature sensor that is connected internally to ADC4. This means you can read the chip’s temperature using the ADC, just like you would with an external analog sensor.

This sensor measures the temperature of the RP2350 chip itself. It does not reflect the room temperature accurately, especially if the chip is under load and heating up.

Control Pins

These pins control the board’s power behavior and can be used to reset or shut down the chip.

-

3V3(EN) is the enable pin for the onboard 3.3V regulator. Pulling this pin low will disable the 3.3V power rail and effectively turn off the RP2350.

-

RUN is the reset pin for the RP2350. It has an internal pull-up resistor and stays high by default. Pulling it low will reset the microcontroller. This is helpful if you want to add a physical reset button or trigger a reset from another device.

Setup

Picotool

picotool is a tool for working with RP2040/RP2350 binaries, and interacting with RP2040/RP2350 devices when they are in BOOTSEL mode.

Tip

Alternatively, you can download the pre-built binaries of the SDK tools from here, which is a simpler option than following these steps.

Here’s a quick summary of the steps I followed:

# Install dependencies

sudo apt install build-essential pkg-config libusb-1.0-0-dev cmake

mkdir embedded && cd embedded

# Clone the Pico SDK

git clone https://github.com/raspberrypi/pico-sdk

cd pico-sdk

git submodule update --init lib/mbedtls

cd ../

# Set the environment variable for the Pico SDK

PICO_SDK_PATH=/MY_PATH/embedded/pico-sdk

# Clone the Picotool repository

git clone https://github.com/raspberrypi/picotool

Build and install Picotool

cd picotool

mkdir build && cd build

# cmake ../

cmake -DPICO_SDK_PATH=/MY_PATH/embedded/pico-sdk/ ../

make -j8

sudo make install

On Linux you can add udev rules in order to run picotool without sudo:

cd ../

# In picotool cloned directory

sudo cp udev/60-picotool.rules /etc/udev/rules.d/

Rust Targets

To build and deploy Rust code for the RP2350 chip, you’ll need to add the appropriate targets:

rustup target add thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

rustup target add riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

probe-rs - Flashing and Debugging Tool

probe-rs is a modern, Rust-native toolchain for flashing and debugging embedded devices. It supports ARM and RISC-V targets and works directly with hardware debug probes. When you use a Debug Probe with the Pico 2, probe-rs is the tool you rely on for both flashing firmware and debugging.

Install probe-rs using the official installer script:

curl -LsSf https://github.com/probe-rs/probe-rs/releases/latest/download/probe-rs-tools-installer.sh | sh

For latest installation instructions, better refer to the official probe-rs documentation.

By default, debug probes on Linux can only be accessed with root privileges. To avoid using sudo for every command, you should install the appropriate udev rules that allow regular users to access the probe. Follow the instructions provided here.

Quick summary:

- Download the udev rules file from the probe-rs repository

- Copy it to

/etc/udev/rules.d/ - Reload udev rules with

sudo udevadm control --reload - Unplug and replug your Debug Probe

After this setup, you can use probe-rs without root privileges.

Quick Start

Before diving into the theory and concepts of how everything works, let’s jump straight into action. Use this simple code to turn on the onboard LED of the Pico2.

We’ll use Embassy, a Rust framework built for microcontrollers like the Raspberry Pi Pico 2. Embassy lets you write async code that can handle multiple tasks at the same time; like blinking an LED while reading a button press, without getting stuck waiting for one task to finish before starting another.

The following code creates a blinking effect by switching the pin’s output between high (on) and low (off) states. As we mentioned in the pinout section, the Pico 2 has its onboard LED connected to GPIO pin 25. In this program, we configure that pin as an Output pin (we configure a pin as Output whenever we want to control something like turning LEDs on/off, driving motors, or sending signals to other devices) with a low (off) initial state.

The code snippet

We’re looking at just the main function code here. There are other initialization steps and imports required to make this work. We’ll explore these in depth in the next chapter to understand what they do and why they’re needed. For now, our focus is just to see something working in action. You can clone the quick start project I created and run it to get started immediately.

Important

This code is incompatible with the Pico 2 W variant. On the Pico 2 W, GPIO25 is dedicated to controlling the wireless interface, we will need to follow a different procedure to control the onboard LED.

#[embassy_executor::main]

async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) {

let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default());

// The onboard LED is actually connected to pin 25

let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_25, Level::Low);

loop {

led.set_high(); // Turn on the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

led.set_low(); // Turn off the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

}

}Clone the Quick start project

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-quick

cd pico2-quick

How to Run?

To Flash your application onto the Pico 2, press and hold the BOOTSEL button. While holding it, connect the Pico 2 to your computer using a micro USB cable. You can release the button once the USB is plugged in.

# Run the program

cargo run

This will flash (write) our program into the Pico 2’s memory and run it automatically. If successful, you should see the onboard LED blinking at regular intervals. If you encounter any errors, verify that you have set up your development environment correctly and connected the Pico properly. If you’re still unable to resolve the issue, please raise a GitHub issue with details so i can update and improve this guide

With Debug Probe

If you’re using a debug probe, you don’t need to press the BOOTSEL button. You can just run cargo flash or cargo embed instead. These commands are covered in detail later in the book, though you can jump ahead to the Debug Probe chapter if you’d like to explore them now.

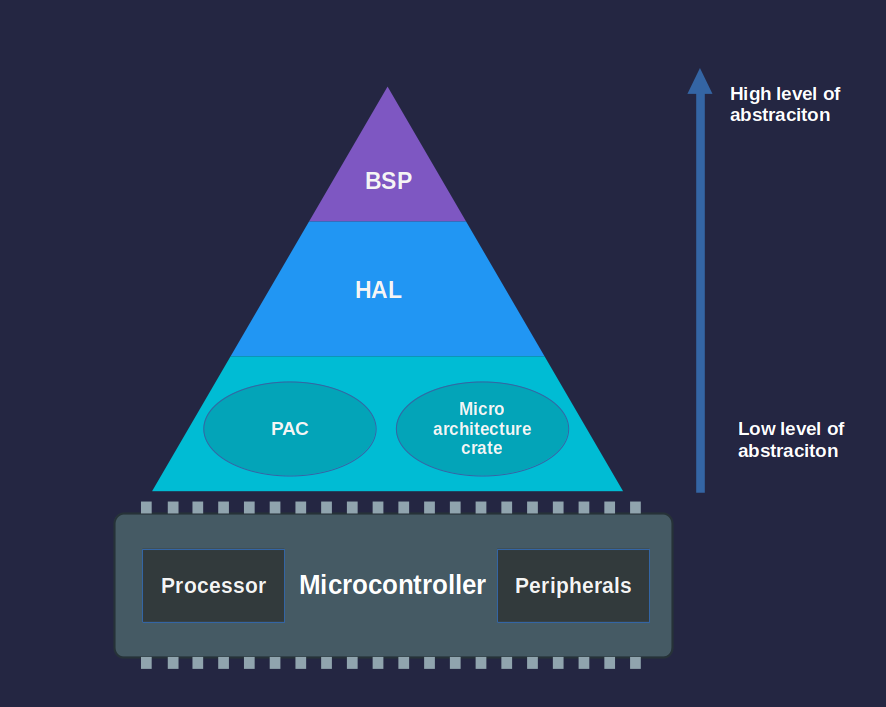

Abstraction Layers

When working with embedded Rust, you will often come across terms like PAC, HAL, and BSP. These are the different layers that help you interact with the hardware. Each layer offers a different balance between flexibility and ease of use.

Let’s start from the highest level of abstraction down to the lowest.

Board Support Package (BSP)

A BSP, also referred as Board Support Crate in Rust, tailored to specific development boards. It combines the HAL with board-specific configurations, providing ready to use interfaces for onboard components like LEDs, buttons, and sensors. This allows developers to focus on application logic instead of dealing with low-level hardware details. Since there is no popular BSP specifically for the Raspberry Pi Pico 2, we will not be using this approach in this book.

Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

The HAL sits just below the BSP level. If you work with boards like the Raspberry Pi Pico or ESP32 based boards, you’ll mostly use the HAL level. HALs are typically written for the specific chip (like the RP2350 or ESP32) rather than for individual boards, which is why the same HAL can be used across different boards that share the same microcontroller. For Raspberry Pi’s family of microcontrollers, there’s the rp-hal crate that provides this hardware abstraction.

The HAL builds on top of the PAC and provides simpler, higher-level interfaces to the microcontroller’s peripherals. Instead of handling low-level registers directly, HALs offer methods and traits that make tasks like setting timers, setting up serial communication, or controlling GPIO pins easier.

HALs for the microcontrollers usually implement the embedded-hal traits, which are standard, platform-independent interfaces for peripherals like GPIO, SPI, I2C, and UART. This makes it easier to write drivers and libraries that work across different hardware as long as they use a compatible HAL.

Embassy for RP

Embassy sits at the same level as HAL but provides an additional runtime environment with async capabilities. Embassy (specifically embassy-rp for Raspberry Pi Pico) is built on top of the HAL layer and provides an async executor, timers, and additional abstractions that make it easier to write concurrent embedded applications.

Embassy provides a separate crate called embassy-rp specifically for Raspberry Pi microcontrollers (RP2040 and RP235x). This crate builds directly on top of the rp-pac (Raspberry Pi Peripheral Access Crate).

Throughout this book, we will use both rp-hal and embassy-rp for different exercises.

Note

The layers below the HAL are rarely used directly. In most cases, the PAC is accessed through the HAL, not on its own. Unless you are working with a chip that does not have a HAL available, there is usually no need to interact with the lower layers directly. In this book, we will focus on the HAL layer.

Peripheral Access Crate (PAC)

PACs are the lowest level of abstraction. They are auto-generated crates that provide type-safe access to a microcontroller’s peripherals. These crates are typically generated from the manufacturer’s SVD (System View Description) file using tools like svd2rust. PACs give you a structured and safe way to interact directly with hardware registers.

Raw MMIO

Raw MMIO (memory-mapped IO) means directly working with hardware registers by reading and writing to specific memory addresses. This approach mirrors traditional C-style register manipulation and requires the use of unsafe blocks in Rust due to the potential risks involved. We will not touch this area; I haven’t seen anyone using this approach.

Project Template with cargo-generate

“cargo-generate is a developer tool to help you get up and running quickly with a new Rust project by leveraging a pre-existing git repository as a template.”

Read more about here.

Prerequisites

Before starting, ensure you have the following tools installed:

- Rust

- cargo-generate for generating the project template.

Install the OpenSSL development package first because it is required by cargo-generate:

sudo apt install libssl-dev

You can install cargo-generate using the following command:

cargo install cargo-generate

Step 1: Generate the Project

Run the following command to generate the project from the template:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

This will prompt you to answer a few questions: Project name: Name your project. HAL choice: You can choose between embassy or rp-hal.

Step 2: Default LED Blink Example

By default, the project will be generated with a simple LED blink example. The code structure may look like this:

src/main.rs: Contains the default blink logic.

Cargo.toml: Includes dependencies for the selected HAL.

Step 3: Choose Your HAL and Modify Code

Once the project is generated, you can decide to keep the default LED blink code or remove it and replace it with your own code based on the HAL you selected.

Removing Unwanted Code

You can remove the blink logic from src/main.rs and replace it with your own code. Modify the Cargo.toml dependencies and project structure as needed for your project.

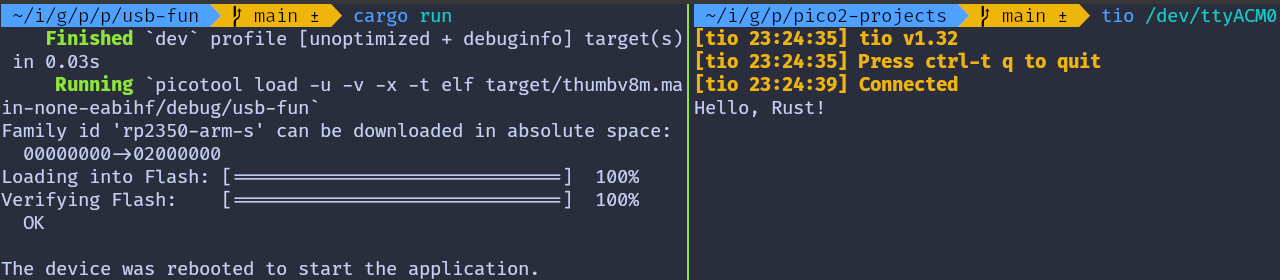

Running the program

Before we explore further examples, let’s cover the general steps to build and run any program on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2. The Pico 2 contains both ARM Cortex-M33 and Hazard3 RISC-V processors, and we’ll provide instructions for both architectures.

Note: These commands should be run from your project folder. This is included here as a general step to avoid repetition. If you haven’t created a project yet, begin with the Quick Start or Blink LED section.

Build and Run for ARM

Use this command to build and run programs on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 in ARM mode, utilizing the Cortex-M33 processors.

# build the program

cargo build --target=thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

To Flash your application onto the Pico 2, press and hold the BOOTSEL button. While holding it, connect the Pico 2 to your computer using a micro USB cable. You can release the button once the USB is plugged in.

# Run the program

cargo run --target=thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

Note

The example codes include a runner configuration in the

.cargo/config.tomlfile, defined as:runner = "picotool load -u -v -x -t elf". This means that when you executecargo run, it actually invokes thepicotoolwith theloadsubcommand to flash the program.

Build and Run for RISC-V

Use this command to build and run programs on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 n RISC-V mode, utilizing the Hazard3 processors.

Important

This book focuses on ARM. Some examples may need changes before they work on RISC V mode. For simplicity, it is recommended to follow the ARM workflow while reading this book.

# build the program

cargo build --target=riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

Follow the same BOOTSEL steps as described above.

# Run the program

cargo run --target=riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

With Debug Probe

When using a Debug Probe, you can flash your program directly onto the Pico 2 with:

# cargo flash --chip RP2350

# cargo flash --chip RP2350 --release

cargo flash --release

If you want to flash your program and also view its output in real time, use:

# cargo embed --chip RP2350

# cargo embed --chip RP2350 --release

cargo embed --release

cargo-embed is a more advanced version of cargo-flash. It can flash your program, and it can also open an RTT terminal and a GDB server.

Help & Troubleshooting

If you face any bugs, errors, or other issues while working on the exercises, here are a few ways to troubleshoot and resolve them.

1. Compare with Working Code

Check the complete code examples or clone the reference project for comparison. Carefully review your code and Cargo.toml dependency versions. Look out for any syntax or logic errors. If a required feature is not enabled or there is a feature mismatch, make sure to enable the correct features as shown in the exercise.

If you find a version mismatch, either adjust your code(research and find a solution; it’s a great way for you to learn and understand things better) to work with the newer version or update the dependencies to match the versions used in the tutorial.

2. Search or Report GitHub Issues

Visit the GitHub issues page to see if someone else has encountered the same problem: https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico-pico/issues?q=is%3Aissue

If not, you can raise a new issue and describe your problem clearly.

3. Ask the Community

The Rust Embedded community is active in the Matrix Chat. The Matrix chat is an open network for secure, decentralized communication.

Here are some useful Matrix channels related to topics covered in this book:

-

Embedded Devices Working Group

#rust-embedded:matrix.org

General discussions around using Rust for embedded development. -

RP Series Development

#rp-rs:matrix.org

For Rust development and discussions around the Raspberry Pi RP series chips. -

Debugging with Probe-rs

#probe-rs:matrix.org

For support and discussion around the probe-rs debugging toolkit. -

Embedded Graphics

#rust-embedded-graphics:matrix.org

For working withembedded-graphics, a drawing library for embedded systems.

You can create a Matrix account and join these channels to get help from experienced developers.

You can find more community chat rooms in the Awesome Embedded Rust - Community Chat Rooms section.

4. Discord

There is an unofficial Discord community for Embedded Rust where you can ask questions, discuss topics, share your experiences, and showcase your projects. It is especially useful for learners and general discussion.

Keep in mind that most HAL and embedded ecosystem maintainers are more active on Matrix. Still, this Discord server can be a good place to learn and interact with others.

Join here: https://discord.gg/NHenanPUuG

Debug Probe for Raspberry Pi Pico 2

Pressing the BOOTSEL button every time you want to flash a new program is annoying. On devboards like the ESP32 DevKit this step is mostly automatic because the devboard can reset the chip into bootloader mode when needed. The Pico 2 does not have this feature, but you can get the same convenience and even more capability by using a debug probe.

This chapter explains why a debug probe is helpful, and step-by-step how to set one up and use it to flash and debug your Pico 2 without pressing BOOTSEL each time.

Raspberry Pi Debug Probe

The Raspberry Pi Debug Probe is the official tool recommended for SWD debugging on the Pico and Pico 2. It is a small USB device that acts as a CMSIS-DAP adapter. CMSIS-DAP is an open standard for debuggers that lets your computer talk to microcontrollers using the SWD protocol.

The probe provides two main features:

-

SWD (Serial Wire Debug) interface - This connects to the Pico’s debug pins and is used to flash firmware and perform real time debugging. You can set breakpoints, inspect variables, and debug your program just like you would in a normal desktop application.

-

UART bridge - This provides a USB to serial connection so you can view console output or communicate with the board.

Both features work through the same USB cable that goes into your computer, which keeps the setup simple because you do not need a separate UART device.

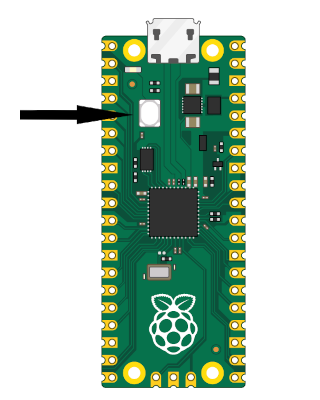

Soldering SWD Pins

Before you can connect the Debug Probe to the Pico 2, you need to make the SWD pins accessible. These pins are located at the bottom edge of the Pico board, in a small 3-pin debug header separate from the main GPIO pins.

Once the SWD pins are soldered, your Pico is ready to connect to the Debug Probe.

Preparing Debug Probe

Your Debug Probe may not ship with the latest firmware, especially the version that adds support for the Pico 2 (RP2350 chip). Updating the firmware is recommended before you start.

The official Raspberry Pi documentation provides clear instructions for updating the Debug Probe. Follow the steps provided here.

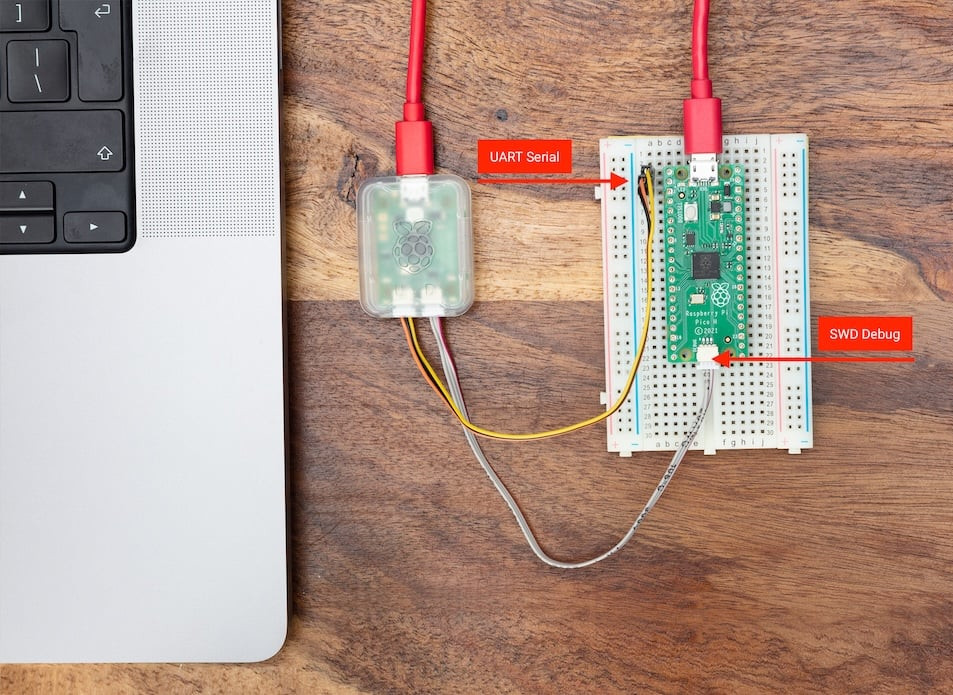

Connecting Pico with Debug Probe

The Debug Probe has two ports on its side:

- D port - For the SWD (debug) connection

- U port - For the UART (serial) connection

SWD Connection (Required)

The SWD connection is what allows flashing firmware and using a debugger. Use the JST to Dupont cable that comes with your Debug Probe.

Connect the wires from the Debug Probe’s D port to the Pico 2 pins as follows:

| Probe Wire | Pico 2 Pin |

|---|---|

| Orange | SWCLK |

| Black | GND |

| Yellow | SWDIO |

Make sure the Pico 2 SWD pins are properly soldered before you attempt the connection.

UART Connection (Optional)

The UART connection is useful if you want to see serial output (like println! logs from Rust) in your computer’s terminal. This is separate from the SWD connection.

Connect the wires from the Debug Probe’s U port to the Pico 2 pins:

| Probe Wire | Pico 2 Pin | Physical Pin Number |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow | GP0 (TX on Pico) | Pin 1 |

| Orange | GP1 (RX on Pico) | Pin 2 |

| Black | GND | Pin 3 |

You can use any GPIO pins configured for UART, but GP0 and GP1 are the Pico’s default UART0 pins.

Powering the Pico

The Debug Probe does not supply power to the Pico 2, it only provides the SWD and UART signals. To power the Pico 2, connect the Debug Probe to your PC through its USB port, then power the Pico 2 separately through its own USB connection. Both devices must be powered for debugging to work properly.

Final Setup

Once connected:

- Plug the Debug Probe into your computer via USB

- Ensure your Pico 2 is powered

- The Debug Probe’s red LED should light up, indicating it has power

- Your setup is ready - no BOOTSEL button pressing needed from now on

You can now flash and debug your Pico 2 directly through your development environment without any manual intervention.

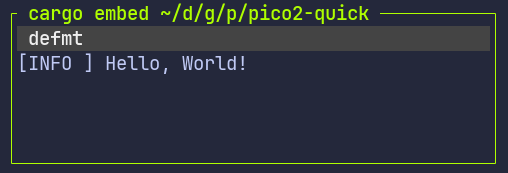

Test it

To verify that your Debug Probe and Pico 2 are connected correctly, you can use the quick start project. Flash it and test that everything works.

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-quick

cd pico2-quick

You cannot just use cargo run like we did before, unless you modified the config.toml. Because the quick start project is set up to use picotool as its runner. You can comment out the picotool runner and enable the probe-rs runner. Then you can use the cargo run command.

Or more simply (i recommend this), you can just use the following commands provided by probe-rs. This will flash your program using the Debug Probe:

cargo flash

# or

cargo flash --release

cargo embed

You can use cargo embed to flash your program and watch the log output in your terminal. The quick start project is already set up to send its log messages over RTT, so you do not need to configure anything before trying it out.

cargo embed

# or

cargo embed --release

If RTT is new to you, we will explain it later, but for now you can simply run the command to see your program run and print logs.

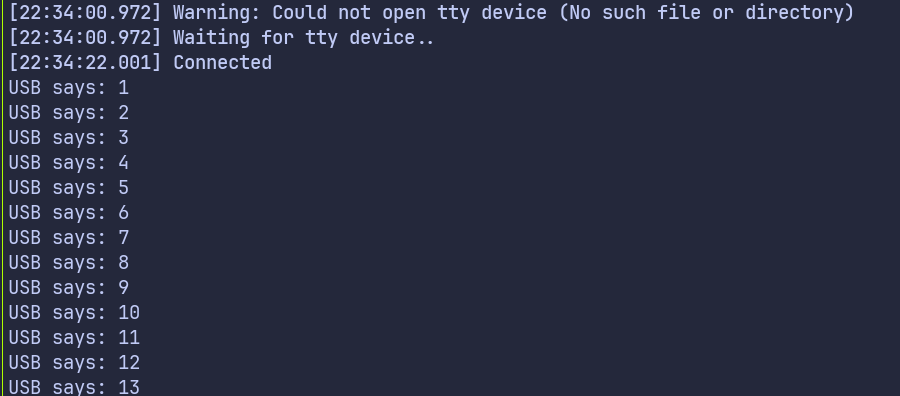

If everything works, you should see the “Hello, World!” message in the system terminal.

Reference

Real-Time Transfer (RTT)

When developing embedded systems, you need a way to see what’s happening inside your program. On a normal computer, you would use println! to print messages to the terminal. But on a microcontroller, there’s no screen or terminal attached. Real-Time Transfer (RTT) solves this problem by letting you print debug messages and logs from your microcontroller to your computer.

What is RTT?

RTT is a communication method that lets your microcontroller send messages to your computer through the debug probe you’re already using to flash your programs.

When you connect the Raspberry Pi Debug Probe to Pico, you’re creating a connection that can do two things:

- Flash new programs onto the chip

- Read and write the chip’s memory

RTT uses this memory access capability. It creates special memory buffers on your microcontroller, and the debug probe reads these buffers to display messages on your computer. This happens in the background while your program runs normally.

Using Defmt for Logging

Defmt (short for “deferred formatting”) is a logging framework designed specifically for resource-constrained devices like microcontrollers. In your Rust embedded projects, you’ll use defmt to print messages and debug your programs.

Defmt achieves high performance using deferred formatting and string compression. Deferred formatting means that formatting is not done on the machine that’s logging data but on a second machine.

Your Pico sends small codes instead of full text messages. Your computer receives these codes and turns them into normal text. This keeps your firmware small and avoids slow string formatting on the microcontroller.

You can add the defmt crate in your project:

defmt = "1.0.1"

Then use it like this:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use defmt::{info, warn, error};

...

info!("Starting program");

warn!("You shall not pass!");

error!("Something went wrong!");

}Defmt RTT

By itself, defmt doesn’t know how to send messages from your Pico to your computer. It needs a transport layer. That’s where defmt-rtt comes in.

The defmt-rtt crate connects defmt to RTT, so your log messages get transmitted through the debug probe to your computer.

You can add the defmt-rtt crate in your project:

defmt-rtt = "1.0"

Tip

To see RTT and defmt logs, you need to run your program using probe-rs tools like the

cargo embedcommand. These tools automatically open an RTT session and show the logs in your terminal

Then include it in your code:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use defmt_rtt as _;

}The line sets up the connection between defmt and RTT. You don’t call any functions from it directly, but it needs to be imported to make it work.

Panic Messages with Panic-Probe

When your program crashes (panics), you want to see what went wrong. The panic-probe crate makes panic messages appear through defmt and RTT.

You can add the panic-probe crate in your project:

# The print-defmt feature - tells panic-probe to use defmt for output.

panic-probe = { version = "1.0", features = ["print-defmt"] }

Then include it in your code:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use panic_probe as _;

}You can manually trigger a panic to see how panic messages work. Try adding this to your code:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

panic!("something went wrong");

}Async In Embedded Rust

When I first started this book, I wrote most of the examples using rp-hal only. In this revision, I have rewritten the book to focus mainly on async programming with Embassy. The official Embassy book already has good documentation, but I want to give a short introduction here. Let’s have a brief look at async and understand why it’s so valuable in embedded systems.

Imagine You’re Cooking Dinner

If you’re familiar with concurrency and async concepts, you don’t need this analogy; Embassy is basically like Tokio for embedded systems, providing an async runtime. If you’re new to async, let me explain with this analogy.

You are making dinner and you put water on to boil. Instead of standing there watching, you chop vegetables. You glance at the pot occasionally, and when you see bubbles, you’re ready for the next step. Now while the main dish cooks, you prepare a side dish in another pan. You even check a text message on your phone. You’re one person constantly moving between tasks, checking what needs attention, doing work whenever something is ready, and never just standing idle waiting.

That’s async programming. You’re the executor, constantly deciding what needs attention. Each cooking task is an async operation. The stove does its heating without you watching it. That’s the non-blocking wait. You don’t freeze in place staring at boiling water. You go do other productive work and come back when it’s ready. The key insight is efficient orchestration: one person (the executor), multiple waiting tasks, and you’re always doing something useful by switching your attention to whatever is ready right now. This is exactly what async programming does for your microcontroller.

Different Approaches

In embedded systems, your microcontroller spends a lot of time waiting. It waits for a button press, for a timer to expire, or for an LED to finish blinking for a set duration. Without async, you have two main approaches.

Blocking

The first approach is blocking code. Your program literally stops and waits. If you’re waiting for a button press, your code sits in a loop checking if the button state has changed. During this time, your microcontroller can’t do anything else. It can’t blink an LED, it can’t check other buttons, it can’t respond to timers. All of your processor’s power is wasted in a tight loop asking “is it ready yet?” over and over again.

Interrupt

The second approach is using interrupts directly. When hardware events happen, like a button being pressed or a timer expiring, the interrupt handler runs. This is better because your main code can keep running, but interrupt-based code quickly becomes complex and error-prone. You need to carefully manage shared state between your main code and interrupt handlers.

Do not worry about interrupts for now. We will go into them in more depth in later chapters.

Async

Async programming gives you the best of both worlds. Your code looks clean and sequential, like blocking code, but it doesn’t actually block. When you await something, your code says “I need to wait for this, but feel free to do other work in the meantime.” The async runtime, which Embassy provides for us, handles all the complexity of switching between tasks efficiently.

How Async Works in Rust

When you write an async function in Rust, you use the async keyword before fn. Inside that function, you can use the await keyword on operations that might take time. Here’s what it looks like:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

async fn blink_led(mut led: Output<'static>) {

loop {

led.set_high();

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

led.set_low();

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

}

}

}The important part is the .await. When you write Timer::after_millis(500).await, you’re telling the runtime “I need to wait 500 milliseconds, but I don’t need the CPU during that time.” The runtime can then go run other tasks. When the 500 milliseconds are up, your task resumes right where it left off.

Think back to our cooking analogy. When you put something on the stove and walk away, you’re essentially “awaiting” it to be ready. You do other things, and when it’s done, you return to that task. Just like you act as the executor in the kitchen, keeping track of what needs attention and when, the async runtime plays the same role for your program.

Embassy

Embassy is one of the popular async runtime that makes all of this work in embedded Rust. It provides the executor that manages your tasks, handles hardware interrupts.

Executor

When you use #[embassy_executor::main], Embassy automatically sets everything up - it runs your tasks, puts the CPU to sleep when everything is waiting, and wakes it up when hardware events occur. The Executor is the coordinator that decides which task to poll when. The executor maintains a queue of tasks that are ready to run. When a task hits await and yields, the executor moves to the next ready task. When there are no tasks ready to run, the executor puts the CPU to sleep. Interrupts wake the executor back up, which then polls any tasks that became ready.

RTIC

RTIC (Real-Time Interrupt-driven Concurrency) is another popular framework for embedded Rust. Unlike Embassy, which provides an async runtime along with hardware drivers, RTIC focuses only on execution and scheduling. In RTIC, you declare tasks with fixed priorities and shared resources upfront, and the framework checks at compile time that resources are shared safely without data races. Higher-priority tasks can preempt lower-priority ones, and the scheduling is handled by hardware interrupts, which makes timing very predictable. This makes RTIC a good fit for hard real-time systems where precise control and determinism matter. You can refer the official RTIC book for more info.

In this book, we will mainly use Embassy.

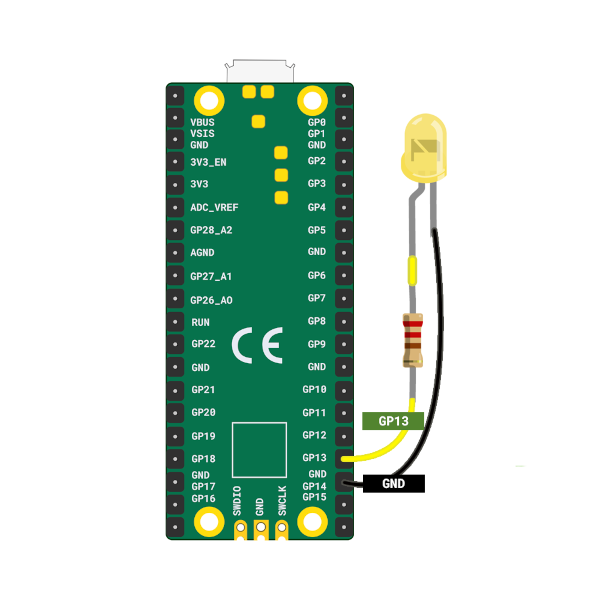

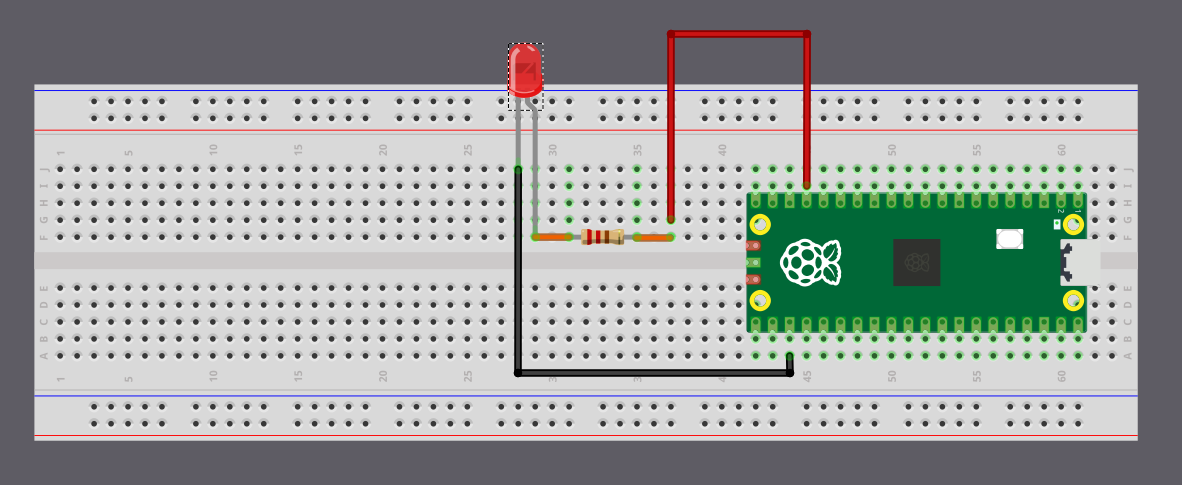

Blinking an External LED

From now on, we’ll use more external parts with the Pico. Before we get there, it helps to get comfortable with simple circuits and how to connect components to the Pico’s pins. In this chapter, we’ll start with something basic: blinking an LED that’s connected outside the board.

Hardware Requirements

- LED

- Resistor

- Jumper wires

Components Overview

-

LED: An LED (Light Emitting Diode) lights up when current flows through it. The longer leg (anode) connects to positive, and the shorter leg (cathode) connects to ground. We’ll connect the anode to GP13 (with a resistor) and the cathode to GND.

-

Resistors: A resistor limits the current in a circuit to protect components like LEDs. Its value is measured in Ohms (Ω). We’ll use a 330 ohm resistor to safely power the LED.

| Pico Pin | Wire | Component |

|---|---|---|

| GPIO 13 |

|

Resistor |

| Resistor |

|

Anode (long leg) of LED |

| GND |

|

Cathode (short leg) of LED |

You can connect the Pico to the LED using jumper wires directly, or you can place everything on a breadboard. If you’re unsure about the hardware setup, you can also refer the Raspberry pi guide.

Tip

On the Pico, the pin labels are on the back of the board, which can feel inconvenient when plugging in wires. I often had to check the pinout diagram whenever I wanted to use a GPIO pin. Use the Raspberry Pi logo on the front as a reference point and match it with the pinout diagram to find the correct pins. Pin positions 2 and 39 are also printed on the front and can serve as additional guides.

LED Blink - Simulation

In this simulation I set the default delay to 5000 milliseconds so the animation is calmer and easier to follow. You can lower it to something like 500 milliseconds to see the LED blink more quickly. When we run the actual code on the Pico, we will use a 500 millisecond delay.

Blink an External LED on the Raspberry Pi Pico with Embedded Rust

Let’s start by creating our project. We’ll use cargo-generate and use the template we prepared for this book.

In your terminal, type:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

You will be asked a few questions:

-

For the project name, you can give anything. We will use external-led.

-

Next, it asks us to Select HAL. We should choose “Embassy”.

-

Then, it will ask whether we want to enable defmt logging. This works only if we use a debug probe, so you can choose based on your setup. Anyway we are not going to write any log in this exercise.

Imports

Most of the required imports are already in the project template. For this exercise, we only need to add the Output struct and the Level enum from gpio:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use embassy_rp::gpio::{Level, Output};

}While writing the main code, your editor will normally suggest missing imports. If something is not suggested or you see an error, check the full code section and add the missing imports from there.

Main Logic

The code is almost the same as the quick start example. The only change is that we now use GPIO 13 instead of GPIO 25. GPIO 13 is where we connected the LED (through a resistor).

Let’s add these code the main function :

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_13, Level::Low);

loop {

led.set_high(); // Turn on the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

led.set_low(); // Turn off the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

}

}We are using the Output struct here because we want to send signals from the Pico to the LED. We set up GPIO 13 as an output pin and start it in the low (off) state.

Note

If you want to read signals from a component (like a button or sensor), you’ll need to configure the GPIO pin as Input instead.

Then we call set_high and set_low on the pin with a delay between them. This switches the pin between high and low, which turns the LED on and off.

The Full code

Here is the complete code for reference:

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use embassy_executor::Spawner;

use embassy_rp as hal;

use embassy_rp::block::ImageDef;

use embassy_rp::gpio::{Level, Output};

use embassy_time::Timer;

//Panic Handler

use panic_probe as _;

// Defmt Logging

use defmt_rtt as _;

/// Tell the Boot ROM about our application

#[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")]

#[used]

pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe();

#[embassy_executor::main]

async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) {

let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default());

let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_13, Level::Low);

loop {

led.set_high(); // Turn on the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

led.set_low(); // Turn off the LED

Timer::after_millis(500).await;

}

}

// Program metadata for `picotool info`.

// This isn't needed, but it's recomended to have these minimal entries.

#[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")]

#[used]

pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [embassy_rp::binary_info::EntryAddr; 4] = [

embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_name!(c"external-led"),

embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"),

embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(),

embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(),

];

// End of fileClone the existing project

You can clone the project I created and navigate to the external-led folder:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-embassy-projects

cd pico2-embassy-projects/external-led

How to Run?

You refer the “Running The Program” section

Blinky Example using rp-hal

In the previous section, we used Embassy. We keep the same circuit and wiring. For this example, we switch to rp-hal to show how both approaches look. You can choose Embassy if you want async support, or rp-hal if you prefer the blocking style. In this book, we will mainly use Embassy.

We will create a new project again with cargo-generate and the same template.

In your terminal, type:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

When it asks you to select HAL, choose “rp-hal” this time.

Imports

The template already includes most imports. For this example, we need to add the OutputPin trait from embedded-hal:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// Embedded HAL trait for the Output Pin

use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin;

}This trait provides the set_high() and set_low() methods we’ll use to control the LED.

Main Logic

If you compare this with the Embassy version, there’s not much difference in how the LED is toggled. The main difference is in how the delay works. Embassy uses async and await, which lets the program pause without blocking and allows other tasks to run in the background. rp-hal uses a blocking delay, which stops the program until the time has passed.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let mut led_pin = pins.gpio13.into_push_pull_output();

loop {

led_pin.set_high().unwrap();

timer.delay_ms(200);

led_pin.set_low().unwrap();

timer.delay_ms(200);

}

}Full code

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use embedded_hal::delay::DelayNs;

use hal::block::ImageDef;

use rp235x_hal as hal;

//Panic Handler

use panic_probe as _;

// Defmt Logging

use defmt_rtt as _;

// Embedded HAL trait for the Output Pin

use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin;

/// Tell the Boot ROM about our application

#[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")]

#[used]

pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe();

/// External high-speed crystal on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 board is 12 MHz.

/// Adjust if your board has a different frequency

const XTAL_FREQ_HZ: u32 = 12_000_000u32;

#[hal::entry]

fn main() -> ! {

// Grab our singleton objects

let mut pac = hal::pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap();

// Set up the watchdog driver - needed by the clock setup code

let mut watchdog = hal::Watchdog::new(pac.WATCHDOG);

// Configure the clocks

//

// The default is to generate a 125 MHz system clock

let clocks = hal::clocks::init_clocks_and_plls(

XTAL_FREQ_HZ,

pac.XOSC,

pac.CLOCKS,

pac.PLL_SYS,

pac.PLL_USB,

&mut pac.RESETS,

&mut watchdog,

)

.ok()

.unwrap();

// The single-cycle I/O block controls our GPIO pins

let sio = hal::Sio::new(pac.SIO);

// Set the pins up according to their function on this particular board

let pins = hal::gpio::Pins::new(

pac.IO_BANK0,

pac.PADS_BANK0,

sio.gpio_bank0,

&mut pac.RESETS,

);

let mut timer = hal::Timer::new_timer0(pac.TIMER0, &mut pac.RESETS, &clocks);

let mut led_pin = pins.gpio13.into_push_pull_output();

loop {

led_pin.set_high().unwrap();

timer.delay_ms(200);

led_pin.set_low().unwrap();

timer.delay_ms(200);

}

}

// Program metadata for `picotool info`.

// This isn't needed, but it's recomended to have these minimal entries.

#[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")]

#[used]

pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [hal::binary_info::EntryAddr; 5] = [

hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_bin_name!(),

hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(),

hal::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"),

hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_homepage_url!(),

hal::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(),

];Clone the existing project

You can clone the project I created and navigate to the external-led folder:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-rp-projects

cd pico2-rp-projects/external-led

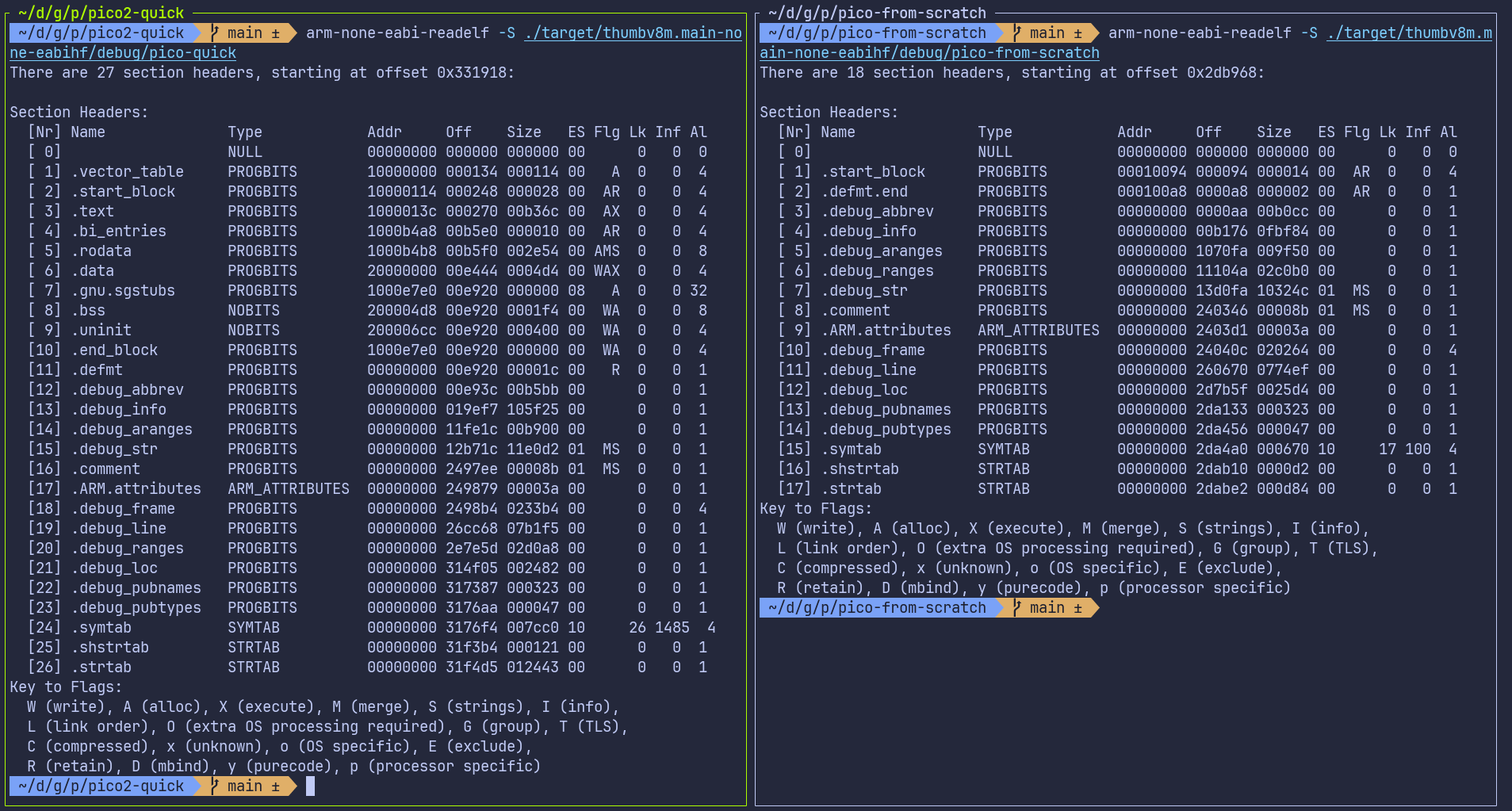

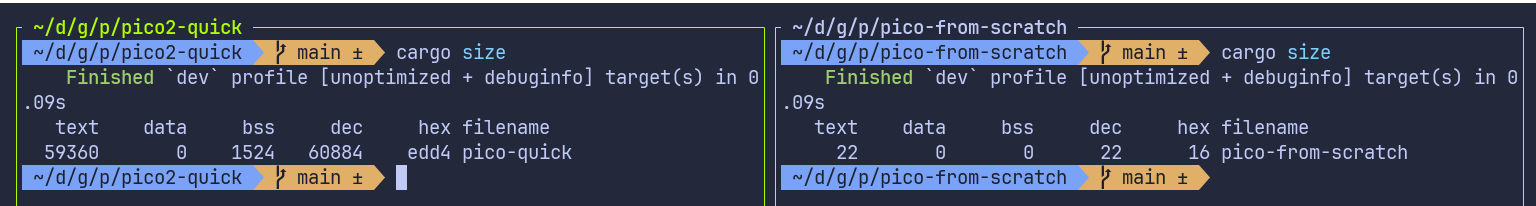

From std to no_std

We have successfully flashed and run our first program, which creates a blinking effect. However, we have not yet explored the code or the project structure in detail. In this section, we will recreate the same project from scratch. I will explain each part of the code and configuration along the way. Are you ready for the challenge?

Tip

If you find this chapter overwhelming, especially if you’re just working on a hobby project, feel free to skip it for now. You can come back to it later after building some fun projects and working through exercises.

Create a Fresh Project

We will start by creating a standard Rust binary project. Use the following command:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

cargo new pico-from-scratch

}At this stage, the project will contain the usual files as expected.

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

Our goal is to reach the following final project structure:

├── build.rs

├── .cargo

│ └── config.toml

├── Cargo.toml

├── memory.x

├── rp235x_riscv.x

├── src

│ └── main.rs

Cross Compilation

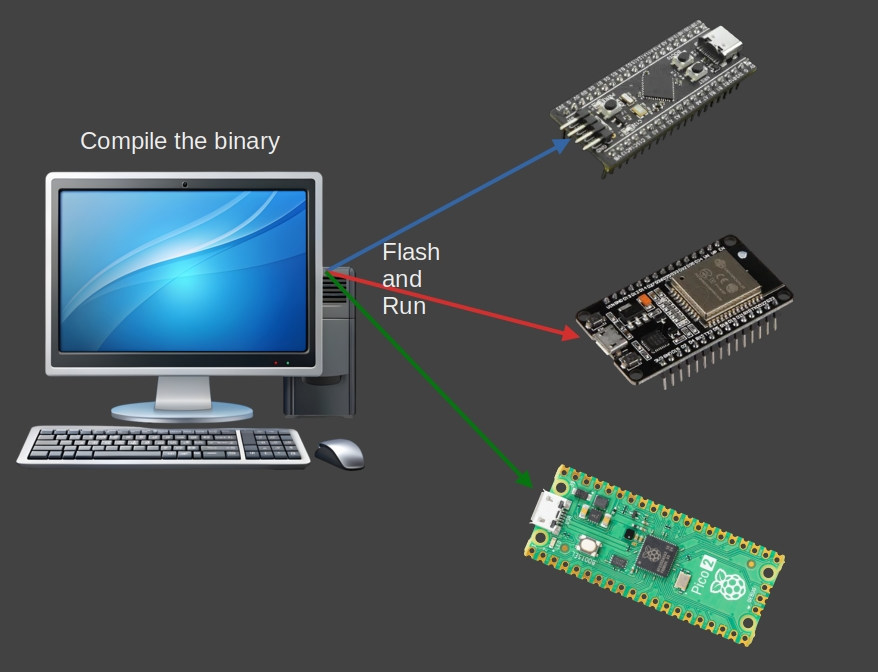

You probably know about cross compilation already. In this section, we’ll explore how this works and what it means to deal with things like target triples. In simple terms, cross compilation is building programs for different machine than the one you’re using.

You can write code on one computer and make programs that run on totally different computers. For example, you can work on Linux and build .exe files for Windows. You can even target bare-metal microcontrollers like the RP2350, ESP32, or STM32.

TL;DR

We have to use either “thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf” or “riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf” as the target when building our binary for the Pico 2.

cargo build --target thumbv8m.main-none-eabihfWe can also configure the target in

.cargo/config.tomlso that we don’t need to type it every time.

Building for Your Host System

Let’s say we are on a Linux machine. When you run the usual build command, Rust compiles your code for your current host platform, which in this case is Linux:

cargo build

You can confirm what kind of binary it just produced using the file command:

file ./target/debug/pico-from-scratch

This will give an output like the following. This tells you it is a 64-bit ELF binary, dynamically linked, and built for Linux.

./target/debug/pico-from-scratch: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, Build...

Cross compiling for Windows

Now let’s say you want to build a binary for Windows without leaving your Linux machine. That’s where cross-compilation comes into play.

First, you need to tell Rust about the target platform. You only have to do this once:

rustup target add x86_64-pc-windows-gnu

This adds support for generating 64-bit Windows binaries using the GNU toolchain (MinGW).

Now build your project again, this time specifying the target:

cargo build --target x86_64-pc-windows-gnu

That’s it. Rust will now create a Windows .exe binary, even though you’re still on Linux. The output binary will be located at target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe

You can inspect the file type like this:

file target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe

It will give you output like this, a 64 bit PE32+ File format file for windows.

target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe: PE32+ executable (console) x86-64, for MS Windows

What Is a Target Triple?

So what’s this x86_64-pc-windows-gnu string all about?

That’s what we call a target triple, and it tells the compiler exactly what kind of output you want. It usually follows this format:

`<architecture>-<vendor>-<os>-<abi>`

But the pattern is not always consistent. Sometimes the ABI part won’t be there. In other cases, even the vendor or both vendor and ABI might be absent. The structure can get messy, and there are plenty of exceptions. If you want to dive deeper into all the quirks and edge cases, check out the article “What the Hell Is a Target Triple?” linked in the references.

Let’s break down what this target triple actually means:

-

Architecture (x86_64): This just means 64-bit x86, which is the type of CPU most modern PCs use. It’s also called AMD64 or x64.

-

Vendor (pc): This is basically a placeholder. It’s not very important in most cases. If it is for mac os, the vendor name will be “apple”.

-

OS (windows): This tells Rust that we want to build something that runs on Windows.

-

ABI (gnu): This part tells Rust to use the GNU toolchain to build the binary.

Reference

Compiling for Microcontroller

Now let’s talk about embedded systems. When it comes to compiling Rust code for a microcontroller, things work a little differently from normal desktop systems. Microcontrollers don’t usually run a full operating system like Linux or Windows. Instead, they run in a minimal environment, often with no OS at all. This is called a bare-metal environment.

Rust supports this kind of setup through its no_std mode. In normal Rust programs, the standard library (std) handles things like file systems, threads, heap allocation, and I/O. But none of those exist on a bare-metal microcontroller. So instead of std, we use a much smaller core library, which provides only the essential building blocks.

The Target Triple for Pico 2

The Raspberry Pi Pico 2 (RP2350 chip), as you already know that it is unique; it contains selectable ARM Cortex-M33 and Hazard3 RISC-V cores . You can choose which processor architecture to use.

ARM Cortex-M33 Target

For ARM mode, we have to use the target [thumbv8m.main-none-eabi](https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustc/platform-support/thumbv8m.main-none-eabi.html):

Let’s break this down:

- Architecture (thumbv8m.main): The Cortex-M33 uses the ARM Thumb-2 instruction set for ARMv8-M architecture.

- Vendor (none): No specific vendor designation.

- OS (none): No operating system - it’s bare-metal.

- ABI (eabi): Embedded Application Binary Interface, the standard calling convention for embedded ARM systems.

To install and use this target:

rustup target add thumbv8m.main-none-eabi

cargo build --target thumbv8m.main-none-eabi

RISC-V Hazard3 Target

For RISC-V mode, use the target [riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf](https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustc/platform-support/riscv32-unknown-none-elf.html):

riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

Let’s break this down:

- Architecture (riscv32imac): 32-bit RISC-V with I (integer), M (multiply/divide), A (atomic), and C (compressed) instruction sets.

- Vendor (unknown): No specific vendor.

- OS (none): No operating system - it’s bare-metal.

- Format (elf): ELF (Executable and Linkable Format), the object file format commonly used in embedded systems.

To install and use this target:

rustup target add riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

cargo build --target riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

In our exercises, we’ll mostly use the ARM mode. Some crates like panic-probe don’t work in RISC-V mode.

Cargo Config

In the quick start, you might have noticed that we never manually passed the –target flag when running the cargo command. So how did it know which target to build for? That’s because the target was already configured in the .cargo/config.toml file.

This file lets you store cargo-related settings, including which target to use by default. To set it up for Pico 2 in ARM mode, create a .cargo folder in your project root and add a config.toml file with the following content:

[build]

target = "thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf"

Now you don’t have to pass –target every time. Cargo will use this automatically.

no_std

Rust has two main foundational crates: std and core.

-

The std crate is the standard library. It gives you things like heap allocation, file system access, threads, and println!.

-

The core crate is a minimal subset. It contains only the most essential Rust features, like basic types (Option, Result, etc.), traits, and few other operations. It doesn’t depend on an operating system or runtime.

When you try to build the project at this stage, you’ll get a bunch of errors. Here’s what it looks like:

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `std`

|

= note: the `thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf` target may not support the standard library

= note: `std` is required by `pico_from_scratch` because it does not declare `#![no_std]`

error: cannot find macro `println` in this scope

--> src/main.rs:2:5

|

2 | println!("Hello, world!");

| ^^^^^^^

error: `#[panic_handler]` function required, but not found

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0463`.

error: could not compile `pico-from-scratch` (bin "pico-from-scratch") due to 3 previous errors

There are so many errors here. Lets fix one by one. The first error says the target may not support the standard library. That’s true. We already know that. The problem is, we didn’t tell Rust that we don’t want to use std. That’s where no_std attribute comes into play.

#![no_std]

The #![no_std] attribute disables the use of the standard library (std). This is necessary most of the times for embedded systems development, where the environment typically lacks many of the resources (like an operating system, file system, or heap allocation) that the standard library assumes are available.

In the top of your src/main.rs file, add this line:

#![no_std]

That’s it. Now Rust knows that this project will only use the core library, not std.

Println

The println! macro comes from the std crate. Since we’re not using std in our project, we can’t use println!. Let’s go ahead and remove it from the code.

Now the code should be like this

#![no_std]

fn main() {

}With this fix, we’ve taken care of two errors and cut down the list. There’s still one more issue showing up, and we’ll fix that in the next section.

Resources:

Panic Handler

At this point, when you try to build the project, you’ll get this error:

error: `#[panic_handler]` function required, but not found

When a Rust program panics, it is usually handled by a built-in panic handler that comes from the standard library. But in the last step, we added #![no_std], which tells Rust not to use the standard library. So now, there’s no panic handler available by default.

In a no_std environment, you are expected to define your own panic behavior, because there’s no operating system or runtime to take over when something goes wrong.

We can fix this by adding our own panic handler. Just create a function with the #[panic_handler] attribute. The function must accept a reference to PanicInfo, and its return type must be !, which means the function never returns.

Add this to your src/main.rs:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(_: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

loop {}

}

}Panic crates

There are some ready-made crates that provide a panic handler function for no_std projects. One simple and commonly used crate is “panic_halt”, which just halts the execution when a panic occurs.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use panic_halt as _;

}This line pulls in the panic handler from the crate. Now, if a panic happens, the program just stops and stays in an infinite loop.

In fact, the panic_halt crate’s code implements a simple panic handler, which looks like this:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

use core::sync::atomic::{self, Ordering};

#[inline(never)]

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

loop {

atomic::compiler_fence(Ordering::SeqCst);

}

}

}You can either use an external crate like this, or write your own panic handler function manually. It’s up to you.

Resources:

no_main

When you try to build at this stage, you’ll get an error saying the main function requires the standard library. What?! (I controlled my temptation to insert a Mr. Bean meme here since not everyone will like meme.) So what now? Where does the program even start?

In embedded systems, we don’t use the regular “fn main” that relies on the standard library. Instead, we have to tell Rust that we’ll bring our own entry point. And for that, we use the no_main attribute.

The #![no_main] attribute is to indicate that the program won’t use the standard entry point (fn main).

In the top of your src/main.rs file, add this line:

#![no_main]

Declaring the Entry Point

Now that we’ve opted out of the default entry point, we need to tell Rust which function to start with. Each HAL crates in the embedded Rust ecosystem provides a special proc macro attribute that allows us to mark the entry point. This macro initializes and sets up everything needed for the microcontroller.

If we were using rp-hal, we could use rp235x_hal::entry for the RP2350 chip. However, we’re going to use Embassy (the embassy-rp crate). Embassy provides the embassy_executor::main macro, which sets up the async runtime for tasks and calls our main function.

The Embassy Executor is an async/await executor designed for embedded usage along with support functionality for interrupts and timers. You can read the official Embassy book to understand in depth how Embassy works.

Cortex-m Run Time

If you follow the embassy_executor::main macro, you’ll see it uses another macro depending on the architecture. Since the Pico 2 is Cortex-M, it uses cortex_m_rt::entry. This comes from the cortex_m_rt crate, which provides startup code and minimal runtime for Cortex-M microcontrollers.

If you run cargo expand in the quick-start project, you can see how the macro expands and the full execution flow. If you follow the rabbit hole, the program starts at the __cortex_m_rt_main_trampoline function. This function calls __cortex_m_rt_main, which sets up the Embassy executor and runs our main function.

To make use of this, we need to add the cortex-m and cortex-m-rt crates to our project. Update the Cargo.toml file:

cortex-m = { version = "0.7.6" }

cortex-m-rt = "0.7.5"

Now, we can add the embassy executor crate:

embassy-executor = { version = "0.9", features = [

"arch-cortex-m",

"executor-thread",

] }

Then, in your main.rs, set up the entry point like this:

use embassy_executor::Spawner;

#[embassy_executor::main]

async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) {}We have changed the function signature. The function must accept a Spawner as its argument to satisfy embassy’s requirements, and the function is now marked as async.

Are we there yet?

Hoorah! Now try building the project - it should compile successfully.

You can inspect the generated binary using the file command:

file target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch

It will show something like this:

target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, with debug_info, not stripped

As you can see, the binary is built for a 32-bit ARM. That means our base setup for Pico is working.

But are we there yet? Not quite. We’ve crossed half the stage - we now have a valid binary ready for Pico, but there’s more to do before we can run it on real hardware.

Resources:

Peripherals

Before we move on to the next part, let’s quickly look at what peripherals are.

In embedded systems, peripherals are hardware components that extend the capabilities of a microcontroller (MCU). They allow the MCU to interact with the outside world by handling inputs and outputs, communication, timing, and more.

While the CPU is responsible for executing program logic, peripherals do the heavy lifting of interacting with hardware, often offloading work from the CPU. This allows the CPU to focus on critical tasks while peripherals handle specialized functions independently or with minimal supervision.

Offloading

Offloading refers to the practice of delegating certain tasks to hardware peripherals instead of doing them directly in software via the CPU. This improves performance, reduces power consumption, and enables concurrent operations. For example:

- A UART peripheral can send and receive data in the background using DMA (Direct Memory Access), while the CPU continues processing other logic.

- A Timer can be configured to generate precise delays or periodic interrupts without CPU intervention.

- A PWM controller can drive a motor continuously without the CPU constantly toggling pins.

Offloading is a key design strategy in embedded systems to make efficient use of limited processing power.

Common Types of Peripherals

Here are some of the most common types of peripherals found in embedded systems:

| Peripheral | Description |

|---|---|

| GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output) | Digital pins that can be configured as inputs or outputs to interact with external hardware like buttons, LEDs, and sensors. |

| UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter) | Serial communication interface used for sending and receiving data between devices, often used for debugging. |

| SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) | High-speed synchronous communication protocol used to connect microcontrollers to peripherals like SD cards, displays, and sensors using a master-slave architecture. |

| I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) | Two-wire serial communication protocol used for connecting low-speed peripherals such as sensors and memory chips to a microcontroller. |

| ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) | Converts analog signals from sensors or other sources into digital values that the microcontroller can process. |

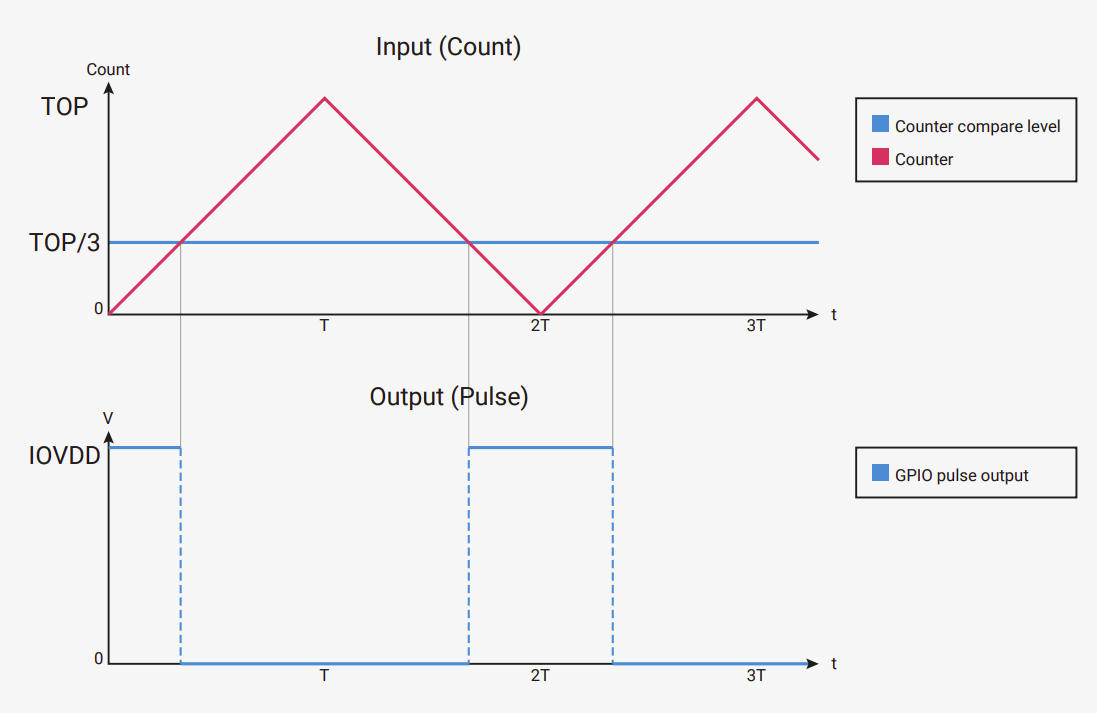

| PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) | Generates signals that can control power delivery, used commonly for LED dimming, motor speed control, and servo actuation. |

| Timer | Used for generating delays, measuring time intervals, counting events, or triggering actions at specific times. |

| RTC (Real-Time Clock) | Keeps track of current time and date even when the system is powered off, typically backed by a battery. |

Peripherals in Rust

In embedded Rust, peripherals are accessed using a singleton model. One of Rust’s core goals is safety, and that extends to how it manages hardware access. To ensure that no two parts of a program can accidentally control the same peripheral at the same time, Rust enforces exclusive ownership through this singleton approach.

The Singleton Pattern

The singleton pattern ensures that only one instance of each peripheral exists in the entire program. This avoids common bugs caused by multiple pieces of code trying to modify the same hardware resource simultaneously.

In embassy, peripherals are also exposed using this singleton model. But we won’t be calling Peripherals::take() directly. Instead, we will use the embassy_rp::init(Default::default()) function. This function takes care of basic system setup and internally calls Peripherals::take() for us. So we get access to all peripherals in a safe and ready-to-use form.

Embassy for Raspberry Pi Pico

We already introduced the concept of HAL in the introduction chapter. For the Pico, we will use the Embassy RP HAL. The Embassy RP HAL targets the Raspberry Pi RP2040, as well as RP235x microcontrollers.

The HAL supports blocking and async peripheral APIs. Using async APIs is better because the HAL automatically handles waiting for peripherals to complete operations in low power mode and manages interrupts, so you can focus on the primary functionality.

Let’s add the embassy-rp crate to our project.

embassy-rp = { version = "0.8.0", features = [

"rp235xa",

] }

We’ve enabled the rp235xa feature because our chip is the RP2350. If we were using the older Pico, we would instead enable the rp2040 feature.

Initialize the embassy-rp HAL